.jpg) |

| The Soane Mausoleum |

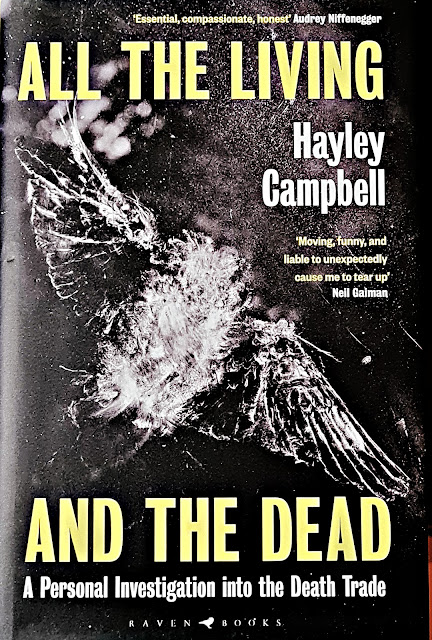

When

I stepped outside on Sunday evening the freezing air was full of large

snowflakes gently sinking to the ground in the windless air. I had been sceptical

when I had seen it earlier on the news but the weatherman had been proved right:

snow was general all over London. It was falling softly upon the East End and,

further westwards, softly falling into the dark mutinous streets of Westminster.

It was falling too upon every part of lonely Old St Pancras churchyard where so

many of the illustrious dead lie buried. It lay thickly drifted on the crooked

crosses and headstones, on the spears of the railings, on the barren thorns. I

felt light headed watching the snow swirl in the darkness at the back of the

house, hearing it fall faintly through the universe and faintly falling, like

the descent of their last end, upon all the living and the dead.

By

next morning the snow had brought the central line to a complete standstill

anywhere east of Liverpool Street and I was obliged to trek to a mainline

station to get into London. On the way to the office I took a detour to Old St

Pancras churchyard to get some photos of the snow before it disappeared. In these

days of global warming snow in London is an evanescent phenomenon; here one

day, transformed to filthy slush the next and gone altogether within 48 hours.

I would have preferred to have gone to Brompton or Kensal Green but I didn’t

have the time and so I made do with St Pancras Gardens, a ten-minute walk from

the office. The snow had stopped falling during the night but the sky was

leaden and the light terrible. I’m not enthralled

with the photos I took, in fact I was so dissatisfied I processed them all in

black and white because I thought they looked better in monochrome. After much

debate I’ve decided to post the original colour versions.

I clambered up an embankment to get a photo of the Soane mausoleum sitting inside its circular railed compound. The mausoleum was designed and built in 1815 by the architect Sir John Soane for his wife Eliza. The couple had met through Eliza’s uncle and ward George Wyatt the builder who had worked with Soane on the rebuilding of Newgate Prison. On the 10th January 1784 Soane took her to the theatre and a few weeks later, on the 7th February she took tea with Soane and a group of friends. Soane began to accompany her regularly to plays and concerts and, on the 21st August 1784, less than 8 months after that first visit to the theatre, they were married at Christ Church in Southwark. It was a happy marriage until they began to have children. They had four sons, two of them died in infancy, the other two survived into adult, both causing their parents endless grief. John, the eldest, was lazy and suffered from infirmity. He was sent to Margate in 1811 to improve his health where he met a woman called Maria Preston. John badgered his father into agreeing to a marriage which he had deep reservations about; the £2000 dowry promised by Maria’s parents failed to materialise and the couple became financially dependent on Soane. Not to be outdone the 20-year-old George wrote to his mother a few weeks later to break the news that he had married behind his parent’s back, making no bones about his reasons, he had done it, he said, “to spite you and father.” Sir John tried to keep his wayward offspring in check by tightly controlling their finances but George threatened to go on stage for a living and disgrace his father if he did not settle £350 a year on him. When the blackmail did not work George took, unsuccessfully, and was imprisoned for debt and fraud. Possibly behind her husband’s back Eliza Soane settled the debt and repaid the embezzled money to get her son out of prison. In September 1815 an article was published in the magazine Champion called ‘The Present Low State of the Arts in England and more particularly of Architecture’. Sir John was the target of an acrimonious attack in the article which, although it had been published anonymously, soon became clear had actually been written by George. His distraught mother wrote on the 13th October 'those are George's doing. He has given me my death blow. I shall never be able to hold up my head again'. She died, quite possibly of heartbreak, on 22 November 1815 and was buried on 1 December. Soane wrote in his diary that he had endured 'the burial of all that is dear to me in this world, and all I wished to live for!' He designed this elaborate mausoleum for his wife and was buried alongside her when he died in 1837.

In

Lights Out for the Territory Iain Sinclair describes the Hardy Tree “with

its cluster of surrounding headstones – like a school of grey fins circling the

massive trunk, feeding on the secretions of the dead.” The tree has become one

of the great myths of London with its backstory of how the young novelist personally

supervised the clearing of the churchyard and the stacking of the headstones

around the Ash tree. The information board by the tree is a little more

circumspect, saying that “the headstones around this Ash tree (Fraxinus

Excelsior) would have been placed here around” the time Hardy was supposedly

overseeing the exhumations in the churchyard. There is no evidence that Hardy

had anything to do with the tree named after him but most people assume that

the gravestones had been arranged around the tree in the first place. A photo of

“St. Pancras churchyard and it’s disturbed gravestones” published in ‘Wonderful

London’ a 1926 book edited by St. John Adcock and published in 1926 shows the

familiar circular arrangement of headstones but with one significant

difference; there is no tree! In 1926 the Hardy tree did not exist. The tree, presumably

self-seeded, has grown since the late 1920’s and is less than one hundred years

old.

Mary Woolstonecraft and William Godwin were married at St Pancras Old Church on 29 March 1797. Mary gave birth to their daughter (the future Mary Shelley) on 30 August 1797 but died of septicaemia 11 days later on 10 September. William was married again in 1801, to Mary Jane Clairmont. When he died in 1836 he choose to be buried with his first wife. Mary Jane joined them in 1841 and all three are commemorated on different faces of what was originally Mary’s memorial. All very modern for the 18th century but Godwin's was a radical household. The post mortem menage a trois were later forcibly split up after passing just 10 years of their eternal rest together when William and Mary were disinterred in 1851 and reburied on the south coast by their grandson Percy. He wanted to grant his mother's wish that she be buried with her parents but didn't want to bury her in grimy Kings Cross. Instead he removed William and Mary's remains (but leaving Mary Jane Clairmont where she was) to a new Shelley tomb at the church of St Peters in Bournemouth.

|

| The Burdett-Coutts memorial sundial |

The adjoining burial grounds of St Pancras and St Giles were closed in 1854. In 1866 a portion of the grounds were sold to the Midland Railway Company to allow the building of a new main line into London and the construction of the new terminus of St Pancras. A scandal ensued during the insensitive exhumation of thousands of bodies and the removal of hundreds of tombs and headstones. In 1874 the railway company approached the vestries of St Pancras and St Giles again to see if they were willing to sell the reminder of the burial ground. This time the public outcry was so strong that the vestries declined to sell and instead proposed laying out a public garden. One of those who took a fervent interest in the future of the disused burial grounds was the philanthropist Baroness Burdett Coutts who felt that as they were “no longer used for their original purpose, they have lost the protection of the living, without securing the sanctity that should protect the dead.” In a letter she later wrote to the vestry of St Pancras she goes into some detail about her motivation for involving herself in the preservation of London’s old burial grounds, explaining that “the feelings and reflections which even an unnamed tombstone is calculated to excite …. would be lost if the graves of the dead were obliterated from the land, for a number of stones huddled together, possibly as carefully as circumstances permitted, cannot convey the same feelings as does a grave, even to the least reflective mind. The mere fact of closing over and stamping out of remembrance the dead renders them lifeless indeed and denies to their memory those tender and salutary lessons so often given in the quiet of ' God's acres.'” The Baroness was determined that the garden should be a memorial to the dead interred there and that it should preserve the principal tombstones and key features of the burial ground. She funded works to conserve headstones and to landscape the gardens but her most lasting contribution to the project was the enormous sundial dedicated to the memory of the illustrious dead placed at the heart of the garden.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)