Clare

shows me the cupboard of knitted hats and baby clothes – mostly white,

different sizes from handmade tiny ones to full-term. The knitted caps serve a

cosmetic purpose here rather than one of warmth, ‘’’: as a baby passes through

the birth canal the planes of its skull overlap so it can fit, but if there is

excess fluid in the baby’s body – as a result of its death – the planes of the

skull can dig into the brain, deforming the head. Clare says she puts the

little cap over it and no one can tell the difference. Next to the bonnets are

brass-hinged wooden jewellery boxes, or so I think, until she stands on her tip

toes to reach one, opens it and it’s empty but for a white lace doily. ‘These

are the coffins for the very little ones’, she says, holding it up so I can see

inside. I had no idea that a bereavement ward existed, let alone coffins for

babies as big as my car keys.

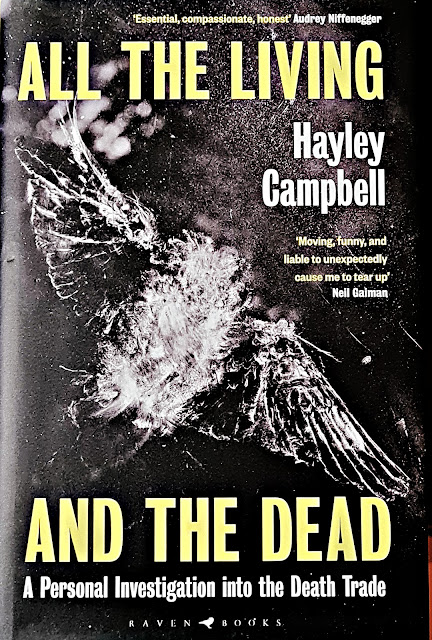

I had started the book with some reservations and Hayley Campbell had quite a bit of work to do to overcome these. I have an issue with book endorsements on newly published hardbacks; no one has had a chance to read and review the book so these endorsements inevitably come from the authors friends or acquaintances. Hayley Campbell has some big hitting friends; on the front cover we get Neil Gaiman and Audrey Niffenegger no less; not many authors would be able to garner accolades from literary heavyweights like these. On the back cover we get, amongst others, Nigella Lawson, Caitlin Doughty, Tuppence Middleton, and Charlie Gilmore. In her opening pages Hayley tells us that her father is Eddie Campbell, the comic book artist who illustrated Alan Moore’s ‘From Hell’. Neil Gaiman is an old friend of the family and Hayley wrote her first book about him. Audrey Niffenegger is her step mother! So, when Niffenegger says the book is “essential, compassionate, honest”, it can’t be taken as an impartial opinion.

Rather annoyingly Niffenegger turns out not to be wrong. Campbell’s book is very good and her own discomfort with the subject matter makes this a very different prospect from anything by Caitlin Doughty or Mary Roach’s breezy ‘Stiff’. There are times in the book when the subject of death threatens to overwhelm the author and a dead baby sends her perilously close to being traumatised. Campbell persists in her journey because, she says, “I think there is urgent, life-changing knowledge to be gained from becoming familiar with death, and from not letting your limits be guided by a fear of unknown things: the knowledge that you can stand to be near it, so that when the time comes you will not let someone you love die alone.” In each of her 12 chapters we meet a death professional, “those who work around death every day” and who are asked to show us “what they do and how they do it – to explore not only the mechanics of an industry, but how it forms a foundation for what it is they do. The Western death industry is predicated on the idea that we cannot, or need not, be there. But if the reason we’re outsourcing this burden is because it’s too much for us, how do they deal with it? They are human too. There is no them and us. It’s just us.” Campbell meets with funeral directors, grave diggers, embalmers, executioners, pathology technologists, death mask sculptors and others. Her book is often funny, sometimes very moving and always fascinating. Highly recommended.

No comments:

Post a Comment