The

tightly packed and heavily populated warrens of the medieval City of London

were full of religious buildings; there was a monastery, priory, nunnery, chapel,

church or cathedral on virtually every street.

In the aftermath of the Great Fire of London the population thinned out as the new streets were widened and regulation was finally imposed on the previously chaotic building practices of the

city. The number of parishes was culled as a result of the falling population. Continuing development

of the city as a commercial and financial rather than residential centre in the

19th century drastically reduced the population of the remaining city parishes

even further, to the point that by the 1850’s there were sometimes more officiating clergy

than worshippers at religious services. The 1860 Union of Benefices Act allowed the Church

of England to rationalise the number of parishes and to dispose of unwanted

buildings and land, including burial grounds and churchyards. By the 1880’s the population of the seven pre 1666 city parishes of St

Olave Jewry, St Martin Pomeroy, St Mildred Poultry, St Mary Colechurch, St Christopher le-Stocks,

St Bartholomew-by-the- Exchange and St Margaret Lothbury had fallen to just

601. All seven parish churches were destroyed by the great fire but only five

of them were rebuilt, all to designs by Sir Christopher Wren; St Martin’s was

joined to St Olaves and St Mary’s to St Mildreds. Only St Margaret Lothbury

still stands, the rest have all been demolished.

|

| St Olave Old Jewry, depicted in the early nineteenth century |

St

Christopher le-Stocks on Threadneedle Street was the first to go, knocked down in

1781 to make way for Sir John Soane’s extension to the Bank of England. St

Bartholomew’s proximity to the Royal Exchange turned into a liability when it

was demolished 1840 in order to improve access to the new exchange building. St

Mildred’s was demolished in 1871 and in 1884 the Ecclesiastical Commissioners

turned their attention to St Olave Old Jewry. The Graphic was appalled; it called St Olave’s “a beautiful

specimen of Wren's architecture,” and appealed “on behalf of the City Church

and Churchyard Protection Society for contributions to its nearly exhausted

funds with which it may oppose these and similar acts of destruction and

desecration.” It did no good; the church was closed in 1887. The St James Gazette was less sentimental

than the Graphic, as St Olave’s “had

no architectural merits, it is impossible to lament over its destruction,” it

said, adding that “doubtless the site, when sold for the erection of one more

block of offices, will bring in money enough to build and endow several

churches in some poor district.” If the Gazette’s feature writer had any

regrets about the demolition of City churches it was “the disappearance of

their picturesque names. It is pleasant, in the wildernesses of industrial and

mercantile London to come across a St. Antholin’s, or St. Olave’s, or St.

Mildred’s, whose titles ‘fall upon the ear like the echo of vanished world.’” Apart

from the tower the church was demolished in 1888. On 18 July 1891 The Star reported that a “placard on

the doors of the church of St. Olave, Old Jewry, gives notice that the fabric

and site of that building will be put up to auction at the Mart.” Two weeks

later the freehold site of the church was offered for sale at the Auction Mart

in Tokenhouse Yard, by Messrs. Edwin Fox and Bousfield and was knocked down for

£22,400. Wren’s tower was retained by the new owners and incorporated into the

new office building they put up on the site of the old churchyard. It still

stands today as the entrance to a much newer office block.

Burials

at St Olave’s continued right up until the 1852 Metropolitan Burial Act

prohibited them, though the number of interments had obviously declined with

the reduction in the living population. Although St Martin Pomeroy, which stood

so close to St Olave’s as to be almost adjacent, had been destroyed in 1666 the

parish burial register continued to be kept separately to St Olave’s until the

early 19th century. The fees for both

parishes were identical; in 1820 £11 for the chancel, vestry and parish vaults and

£1 3s 6d for either churchyard. Prior to the demolition of the church it was

decided to remove all coffins and human remains from the site and rebury them

at the new City of London Cemetery in Ilford. The churchwardens gave notice to

the known relatives of anyone buried within the church or in the churchyard that

they had 3 months to remove their remains. The Ecclesiastical Commissioners had

set up a special fund with which to reimburse the costs of reburial elsewhere,

up to a limit of £10. If no application was received to remove a body by the 1st

December 1887 it would be removed by the Commission for Sewers and reburied in

Ilford. The commission’s workmen dug up the churchyard and broke open the

vaults, removing 216 coffins and 279 cases of bones. The job of taking these to

Ilford was subcontracted to John Shepherd, undertaker of 55 Bishopsgate Street.

At the cemetery the remains were reinterred in a brick lined vault and a new

memorial was erected sacred to all of those formerly buried in the two parishes

but specifically commemorating, in two long lists on either side of the

monument, some of the more worthy deceased. The Frederick

family vault for example contained 27 coffins dating from between 1610 and 1799. Most of them are listed individually

on the memorial including a couple of Frederick baronets, an admiral, a judge,

and Sir Humphrey Weld, Lord Mayor of London in 1608. 61 coffins were

removed from the chancel vault including the Revd Dr Samuel Shepherd.

The

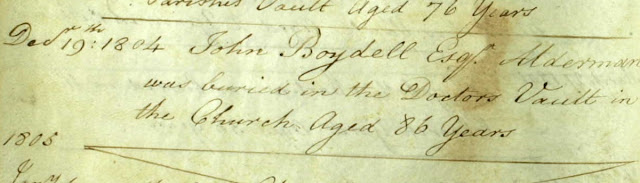

only name I recognised on the memorial was John Boydell the printmaker and

publisher. His wife Elizabeth, who had been his childhood sweetheart and who he

married in 1848, is also listed. According to the St Martin Pomeroy parish

register he was buried on December 19th 1804 in the Doctor’s vault inside the

church. According to Walter Thornbury’s “Old and New London” (1878) the 84 year

old died on the 11th December, his death, “occasioned by a cold, caught at the

Old Bailey Sessions.” He goes on to say

that “it was the regular custom of Mr. Alderman Boydell…, who was a very early

riser, to repair at five o'clock immediately to the pump in Ironmonger Lane.

There, after placing his wig upon the ball at the top, he used to sluice his

head with its water. This well known and highly respected character was one of

the last men who wore a three-cornered hat, commonly called the ‘Egham, Staines,

and Windsor.’” That these crack of dawn, midwinter, open air dousings under the

parish pump didn’t kill him off until he was in his eighties stands testament

to his robust constitution.

Boydell

was born in Shropshire in 1720, the son of a land surveyor. He came to London

in 1740 as an apprentice, to learn the art of engraving. He opened his first

business in 1746 making and selling his own prints. Thornbury’s principal

source for his account of Boydell’s career, ‘Rainy Day’ Smith told him that when

Boydell started publishing “he etched small plates of landscapes, which he

produced in plates of six, and sold for sixpence; and that as there were very

few print-shops at that time in London, he prevailed upon the sellers of

children's toys to allow his little books to be put in their windows. These

shops he regularly visited every Saturday, to see if any had been sold, and to

leave more. His most successful shop was the sign of the 'Cricket Bat,' in

Duke's Court, St. Martin's Lane, where he found he had sold as many as came to

five shillings and sixpence. With this success he was so pleased, that, wishing

to invite the shopkeeper to continue in his interest, he laid out the money in

a silver pencil-case; which article, after he had related the above anecdote,

he took out of his pocket and assured me he never would part with.” He

gradually gave up engraving in favour of making prints of other peoples

designs. He became enormously successful , transforming what had hitherto been

a niche market for imported French prints, into a thriving domestic and export

market in British produced prints.

In

1789 Boydell opened his Shakespeare Gallery on Pall Mall. He commissioned

paintings based on Shakespeare’s works from Britain’s best known artists which

the public paid one shilling to see. The entrance fee was a bargain – the Royal

Academy charged considerably more ‘to prevent the Rooms being filled by

improper Persons’. The real money spinners were the prints of the paintings

produced by a team of 46 printmakers which were available to purchase singly,

as a portfolio or as bound illustrations in a specially commissioned edition of

Shakespeare’s plays. Boydell’s impressive profits enabled him to pay hefty fees

to the artists who produced the paintings. Even Sir Joshua Reynolds, who as

President of the Royal Academy strongly disapproved of Boydell’s gallery and

who thought that prints based on paintings were vulgar, put aside his

objections to the scheme when he was offered 1000 guineas for a single painting

of the three witches from Macbeth.

According to Thornbury George Stevens, the editor of the special edition of

Shakespeare, took it upon himself to persuade Sir Joshua to accept the

commission; “taking a bank-bill of five hundred pounds in his hand, he had an

interview with Sir Joshua, when, using all his eloquence in argument, he, in

the meantime, slipped the bank-bill into his hand; he then soon found that his

mode of reasoning was not to be resisted, and a picture was promised.” The

painter’s scruples completely collapsed in fact and he soon produced 3

paintings for Boydell’s gallery. The most famous of these was a Puck or Robin

Goodfellow painted in 1789. Walpole described it as depicting 'an ugly little

imp (but with some character) sitting on a mushroom half as big as a

mile-stone.' Thornbury, again, describes

the birth of this picture “Mr. Nicholls, of the British Institution, related to

Mr. Cotton that the alderman and his grandfather were with Sir Joshua when

painting the death of Cardinal Beaufort. Boydell was much taken with the

portrait of a naked child, and wished it could be brought into the Shakespeare.

Sir Joshua said it was painted from a little child he found sitting on his

steps in Leicester Square. Nicholls' grandfather then said, 'Well, Mr.

Alderman, it can very easily come into the Shakespeare if Sir Joshua will

kindly place him upon a mushroom, give him fawn's ears, and make a Puck of

him.' Sir Joshua liked the notion, and painted the picture accordingly…. The

merry boy, whom Sir Joshua found upon his door-step, subsequently became a

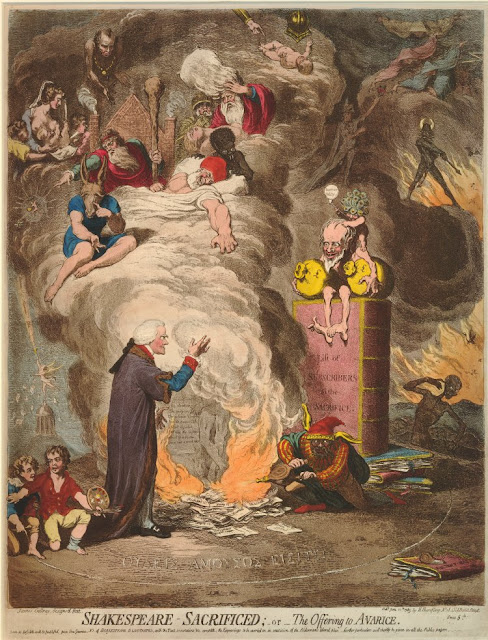

porter at Elliot's brewery, in Pimlico.” Gillray satirised Boydell and the

Shakespeare Gallery ironically using the very medium Boydell had done so much

to popularise, print making. In ‘Shakespeare sacrificed or the offering to

avarice’ Boydell is shown in his alderman’s robes burning the bard’s works,

producing thick clouds of smoke which support travestied figures from the

paintings commissioned for the gallery, watched by a ancient goblin like figure

clutching two large money bags.