Unless

they are particularly unusual, I don’t normally pay much attention to modern

memorials when I am visiting cemeteries. As a general rule of thumb, the more

recent they are the less interesting they will be. A production line headstone

of polished black granite, churned out in a Chinese factory, embellished to

order with photo and trite verses, etched with flowers, football club crest, or

crucifix, and despatched to England in a shipping container from Nanjung or

Guangzhou, will cost less than a grand.

A simple stonemason’s product, made from British stone, with minimal

lettering and decoration will cost you at least four or five times that. There

aren’t many mass produced Chinese memorials in Highgate cemetery though. I

don’t know what the current price is but back in 2018 a grave cost £19,975 plus a £1,850 burial fee. It was, and no doubt

still is, Britain’s most expensive graveyard and anyone who can afford to be

buried here will not baulk at the cost of adorning their final resting place

with a modish headstone; vulgarity is forbidden in Highgate’s middle-class

Elysian Fields.

Walking

around the cemetery a couple of weeks ago I found myself paying attention to

the hitherto ignored headstones of the North London bourgeoisie. In a path by

the boundary wall by Waterlow Park I stumbled across the grave of Andrea Levy.

I paused because I know who Levy is; the author of ‘Small Island’ and ‘The Long

Song’ died of cancer in February 2019, just before the pandemic shut the UK

down, and before she had the chance to draw her retirement pension, at the far

too young age of 62. Her headstone follows the classic template for the new

memorials, a simple slab of dressed black stone with elegant typography

announcing her name and profession, novelist, her dates, 1956 to 2019, and an

enigmatic three-word epitaph - ‘This is life.’ The purpose of these brief

epitaphs is, I assume, to give us a flavour of the deceased’s personality.

Levy’s fails I think because the meaning isn’t clear and so it doesn’t really

tell us anything about her. This is life? What is? Being dead and buried in a

cemetery? Isn’t this death, not life?

Levy was cremated and judging by the size of the plots, this is true of most of the modern memorials. Just across the path from Levy stands the grave marker of Sally Hunter. Squashed up against the boundary wall the plot is only big enough to bury the remains from a cremation. The stone is another plain black rectangle with white lettering giving Sally’s dates, 1958 to 2015, her profession and her epitaph; ‘LAWYER should have been a marine biologist’. It is a much better epitaph, wistful, funny, memorable. Film director Gurinder Chadha, whose movies include ‘Bhaji on the Beach’ and ‘Bend it like Beckham’ explained where the epitaph came from; “Sally was one of my best friends, she fell into Law at university but never wanted to be a lawyer. Her big passion was snorkelling, diving and the sea. she would escape to Egypt, or anywhere she could snorkel, at a drop of a hat. She was a very well read, witty, passionate person who made the wrong choice in career life. We miss her terribly.”

The

headstone of Joe Alvarez is unusual because it mentions that he was a father. In

very stark contrast to the older gravestones in the cemetery, where the

deceased is often defined by their relationships, ‘beloved wife of…’ ‘husband

of…’ ‘…and their children….’ etc., the modern memorials at Highgate are monuments

to bourgeois individualism with no mention of significant others. As though

they lived in a social vacuum, or that they don’t want to share their moment of

glory with anyone else, even if they were married to them for half a century.

At least Joe Alvarez, publisher and press photographer who died of cancer at

the age of 46, mentions the relatively young family he left behind when he died

in 2019.

Next to Alvarez are the remains of Paul Winner (1934-2019). His headstone demonstrates another notable trend amongst some of the modern memorials – apart from his name and dates and an image of the roofline of a distant castle seen over the tops of trees, the only information given are the words ‘Dream Conductor’. I presume this is how Mr Winner liked to see himself but in real life he was a well known PR consultant of Latvian Jewish descent, a keen amateur artist who studied at Oxford, ran his own highly successful PR company, was married with two children and lived in Hampstead. From his obituary in The Times; “When Winner started out at the marketing agency Lonsdale-Hands in 1964, many British company directors did not believe in public relations. Richard Lonsdale-Hands, its patrician chairman, initially did not know what to make of the puckish young man. Winner was given the unpromising job of marketing the White Fish Authority in 1966. The chairman soon revised his view when Winner served up a mouthwatering proposition by phoning newspapers to champion the 100th anniversary of “the marriage of fish and chips”. The date of the centenary is contested, but editors with pages to fill cared not. Winner added fat to the fryer by ensuring that all parliamentary candidates at the 1966 general election had fish and chips delivered to help them through the night. A vinegary package was even sent to the prime minister, Harold Wilson. The campaign generated coverage all over the world, including a leading article in The Times.”

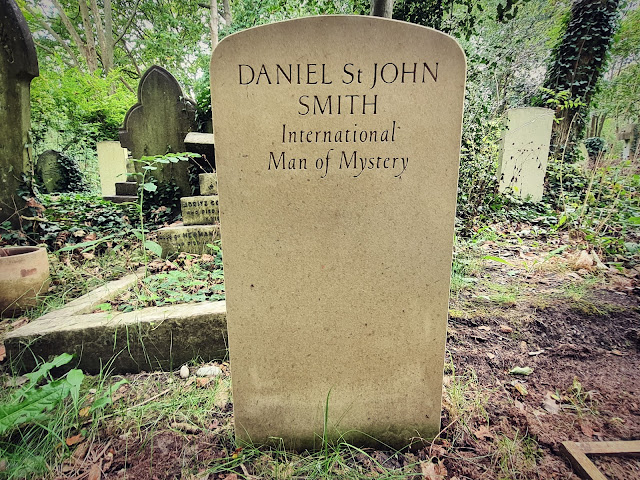

Close

by is the grave of Daniel St John Smith, whose plain headstone gives no dates

and simply states ‘International Man of Mystery’. I could find out absolutely

nothing about this human enigma.

According

to his grave stone George Ross 1935-2011, was a Philosopher, Teacher,

Physicist, Romanian and Nudist. It is another grave marker with a suggestive

but essentially meaningless epitaph; “If…”

His Times obituary says “George Ross was an intellectual bohemian who,

before he applied to leave his native Romania in 1963, was set for a career in

physics. The communist state employed Ross, who graduated fourth in the

country, as a bottle- washer and a glassblower in a light-bulb factory before

letting him go. A kind, emotional man, who spent the rest of his life teaching

physics and philosophy of science, mainly in London, he never abandoned the

high moral principles that made life under a people’s dictatorship unbearable.

Born in 1935 into a wealthy and distinguished Sephardi family in Bucharest, Ross grew up multilingual. One grandfather spoke 14 languages. A second taught him geometry like Socrates taught the slave boy, by drawing lines in the sand with a stick. Ross longed to study philosophy, but since the communist curriculum offered only dialectical materialism, he chose physics, and kept up his real interests, and his wide reading, in private.” At the age of 28 George emigrated with his mother to Israel where he met his future wife Rosemary Emanuel from North London at the Weizmann Institute. Rosemary’s parents threw a lavish wedding for the couple in London; “plunged into synagogue life,” says The Times, “the ardent individualist was shocked by being expected to conform; not a good omen for his married future. Though appropriately learned, he never wanted to be a practising Jew.”

Paul Nathan, 1924 -2016, was apparently a Physiologist and Farmer and judging by the star of David and the pebbles left on his headstone, also Jewish. His epitaph is ‘Eating chocolates and telling stories’. It is relatively easy to find details of his published papers on physiology (‘Antigen Release from the Transplanted Dog Kidney’ 1966 in the Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences when Nathan was based at the Jewish Hospital of Cincinnati) but I couldn’t find many, or indeed any, biographical details.

No

mention of wife or children on the memorial of Ian S. McDonald (1936-2020) is not

due to any reluctance on his part to acknowledge the part they might have

played in his life; he didn’t have any. Although many of the North London bourgeoisie feel

that their life is best summed up by their profession, a little part of them

rebels and wants to be remembered for something more than their career.

McDonald who was a ‘Civil Servant in the MOD Prominent in the Falklands War’

was also, his headstone would have us believe, a Raconteur. He was the official spokesman for the MOD

during the Falklands conflict and was frequently featured on news programmes,

becoming almost a household face for a few months. His restrained style of

delivery, sometimes described as ‘sepulchral’,

but “heavily bespectacled, dark suited and with a penchant for erudite

aphorisms, he gained the public’s confidence and the grudging respect of the

media.”

The saddest epitaph I saw was for a Jonathan Howel Ellis (1959-2020) – “Best project finance lawyer in the world”, a quote attributed to someone called Jon. I hope it wasn’t Jonathan himself who came up with this sad summation of 61 years spent on Earth.

I have to admit I enjoyed looking at the modern headstones I saw when I visited Highgate many years ago.

ReplyDeleteNot just you Bill, I'm getting a lot more views than normal on this - it seems I have seriously underestimated the attraction of modern memorials

DeleteIs this possibly the same Daniel Smith? https://www.thegazette.co.uk/notice/3743102

ReplyDeleteIt could well be - right name, right time but impossible to say for sure because of the lack of information on the headstone.

DeleteIf I was to have a headstone, I would like it to say "a giant among lesser men"

ReplyDeleteBecause you are 6 foot 3?

Deletehttps://www.gocomics.com/peanuts/1957/03/02

ReplyDeleteI thought you were referencing Emily Dickinson but Linus is much funnier. And it would make a good epitaph.

Delete