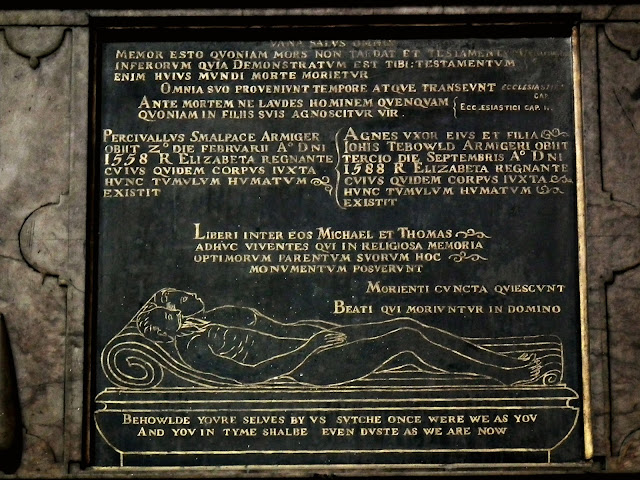

“In the north

transept of Southwark Cathedral, close to the Harvard Chapel, are the monument

and grave of Lionel Lockyer, a seventeenth century quack. The monument is

perhaps the most prominent object in the transept, and includes as its

principal feature a large semi-recumbent figure of the doctor. The face wears

an expression of unctuous self-satisfaction, quite in keeping with what we know

of Lockyer himself.”

Hector A. Colwell M.B. Lond.

What

little we can learn of the life of Lionel Lockyer we have to learn from his

detractors, in particular to his principal rival in the field of patent

medicine, the American alchemist George Starkey (or Eireneaus Philalethes as he

was known in alchemistical circles). In 1664, goaded by Lockyers overwrought

claims for his famous pills, Starkey wrote “A smart Scourge for a silly, sawcy

Fool, an answer to letter at the end of a pamphlet of Lionell Lockyer.” Starkey

clearly hoped his tract would demolish Lockyer’s reputation and fatally undermine

his business but he was to be disappointed.

Not even death managed to do that; in 1824, 150 years after his death,

James Granger reports that Lockyer’s Pills were still being sold by Newbury the

bookseller in St Paul’s Churchyard.

|

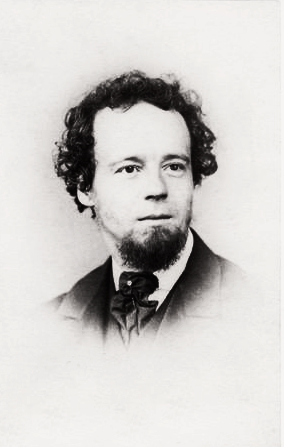

| A contemporary portrait |

From

Starkey we learn that before he took up medicine Lionel Lockyer had been a

tailor and a butcher and that he had learned his medicine from a certain Molton

of Hogg Lane. The first version of his pills, “a very common and churlish

medicine” had been simply produced by dyeing some pills produced from a

solution of the salt of antimony bright red with cochineal and vending them as ‘mercurialis

vitae’. A more refined product, Pilulae Radiis Solis Extractae, one of the key

ingredients of which was supposedly sun beams, made Lockyer a fortune. The

vulgar had trouble with the Latin name so Lockyer, citing a biblical precedence

simply named them after himself; "Absolom

because he had no son to succeed him, he erected a Pillar and called it after

his own name (2 Sam. xviii, 18). And I have had sons, but They are not, and so

I shall call the pill after my own name, Lockier's Pill."' The unsympathetic

Starkey never mentions Lockyer’s loss of his children; at the time it was not perhaps

a noteworthy event.

Lockyer

had a genius for marketing. He supposedly printed upwards of 200,000 copies of

his famous handbill advertising the miraculous qualities of his pilulae which

were a medicine “of a solar nature, dispelling of those causes in our Bodies,

which continued, would not only darken the Lustre, but extinguish the Light of

Our Microcosmical Sun.” The price of this sovereign remedy was 4 shillings a

box, the box stamped with the makers coat of arms and only available from some

forty authorised dealers in town and country and which included “Mrs. Harfords

at the Bible in Heart in Little Britain, Mr. Russel’s in Mugwel Street near

Cripple Gate, Mr. Randal’s at the Three Pigeons, beyond St. Clements Church, in

the Strand, Thomas Virgoes, cutler, upper end of New Fish Street and Mr. Brugis,

printer, next door to Red Lyon Inn, in Newstreet near Fetter Lane.” As was

generally the case this was another pill to cure all ills and even to be taken

by those in full heath as a “preservative against all accidents as contagious

aires, for which it stands Centinel in the body and not permitting any enemy of

nature to enter.” Lockyer’s broadsheet also included case studies demonstrating

the efficacy of his remedy "Mrs. Dixon suffered for two years at least

with a griping, gnawing pain in the belly, and by the use of my Pills, and

God's blessing upon it, was cured; For before she had taken of my Pills six times

she had a live worm come from her by Siege, four yards long; the woman lives in

Dead-man's Place in Southwark, near unto the Colledge Gate. Her age is about

thirty-two years, the worm came from her the latter end of May, 1662. If any

desire to see the worm I have it by me." He also relates the heart warming

story of a young man who “told a friend of mine, that he had the POX, who gave

him two boxes of pills, and in three weeks time he was perfectly cured,

although he scarce went to bed sober all that time, and within three weeks time

he married a wife, and both of them very well to this day."

Lockyer

later added an appendix to his advertisement, a letter supposedly from a “Person

of Quality” which discloses that on June 13, 1664 Lockyer calcined the powder

for his pill before King Charles and the Court at Southampton House. It was

this letter that drew the ire of George Starkey and drove him to compose the “smart

Scourge” in which he poured scorn on Lockyer’s, or his correspondent’s, Latin “I

will take notice first of your false Latine....for which I should take you to

task as a rigid Paedogogue, and nake you untruss for the first fault, your

Breech would be bloudy and too sore to sit on, if for all the lapses committed

in that very short epistle you had (as you deserve) a several lash.”

Locker

died in 1672 leaving a small fortune of £1900 in ready, the leases on four

houses and a quarter share in a ship. As well as a lavish funeral and his ostentatious

monument he left a sizeable amount towards charity. Even in death he could not

resist one last chance to sell his pilulae and his epitaph is little more than

an advertising opportunity;

Here

Lockyer: lies interr'd enough: his name

Speakes

one hath few competitors in fame:

A

name soe Great, soe Generall't may scorne

Inscriptions

whch doe vulgar tombs adorne.

A

diminution 'tis to write in verse

His

eulogies whch most mens mouths rehearse.

His

virtues & his PILLS are soe well known

That

envy can't confine them vnder stone.

But

they'll surviue his dust and not expire

Till

all things else at th'universall fire.

This

verse is lost, his PILL Embalmes him safe

To

future times without an Epitaph