|

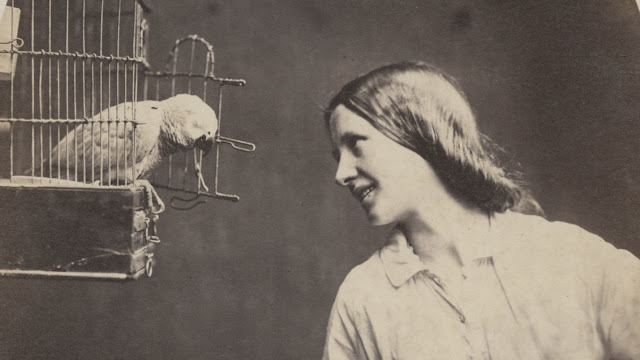

| Don't let him out of the cage! A parrot's bid for freedom leads to death for his erstwhile rescuer |

A parrot on Sunday escaped from a house in Dean's- yard, Westminster, and flew as far as St. John's burial ground, where it alighted on one of the trees. A reward being offered, William Harding, a mason's labourer, of Horseferry-road, procured a ladder, and placing it against the tree on which the parrot was perched ascended it. He left the ladder and held on one of the branches which broke, and he fell head foremost on the edge of a tombstone with such violence that death was instantaneous.

Globe - Monday 01 July 1878

I

am embarrassed to admit it but my initial reaction on reading of William

Harding’s death was to laugh. The laconic version of the dead workman sketch in

the Globe bears too close a resemblance to one of Wile E. Coyotes looney tune misadventures

with Roadrunner not to raise a snigger; the breaking branch, the falling

ladder, William’s stunned stare meeting impassive psittacine gaze whilst

suspended mid-air for the split-second it always seems to take for gravity to

start operating in Warner Brother cartoons.

And then the irony of braining yourself on a tombstone whilst in pursuit

of a parrot. It is one of those ridiculous Victorian deaths, one to rival Henry

Taylor getting himself killed by a coffin in Kensal Green or the poor Hickman’s

managing to accidentally poison the entire family at Sunday lunch with arsenic

stored in a flour bag. A less frantic

version of the same events in the York Herald of 3rd July, whilst still steeped

in bathos, manages to at least sound like a misfortune;

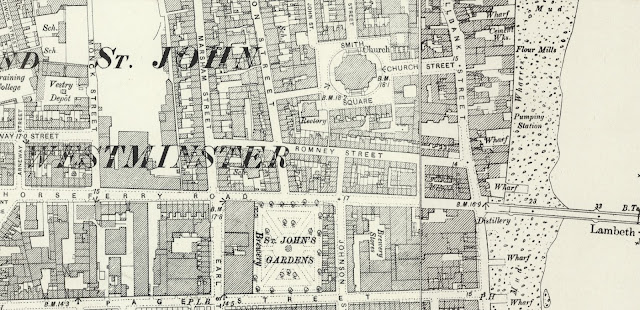

SHOCKING

OCCURRENCE IN WESTMINSTER. Yesterday morning the particulars of a shocking

accident were forwarded to Mr Bedford, the coroner. During Sunday a valuable

parrot effected its escape from a house in Deans-yard, West- minster, and flew

as far as St. John's burial ground, which is situated between Horseferry-road

and Page-street, where it alighted on one of the trees. A reward was offered

for the capture of the bird, and many ineffectual attempts were made to regain

it. The parrot still remaining at the spot, a man named William Harding, a

mason's labourer, of 52, Horseferry-road, about eleven o'clock on Sunday night

procured a ladder, and placing it against the tree on which the parrot was

perched, ascended it. In order to get within reach of the bird, he left the

ladder and held on by one of the branches, which broke with his weight, and he

fell headforemost on the edge of a tombstone, with such violence that death was

instantaneous. His body presented a most sickening appearance, the head being

completely battered in. Deceased, who was about forty years of age, leaves a

widow and five children.

|

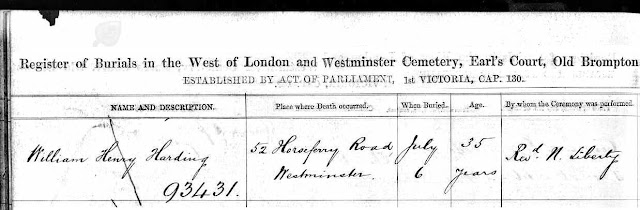

| William's burial record at Brompton Cemetery |

William

Henry Harding died on Sunday 30th June and was buried the following Saturday,

the 6th July, in a common grave in Brompton Cemetery. The officiating clergyman

was the Rev. Nathaniel Liberty, chaplain to the cemetery and to the Brompton

Cancer Hospital (3 years later he buried George Borrow). The burial records

confirms William’s address as 52 Horseferry Road but gives his age as 35 rather

than the 40 reported in the newspapers. With a full name, an address, an

accurate year of birth and a household containing a wife and five children I thought

it would be relatively easy to track down records relating to the family. There were more William Hardings than I

imagined living in Westminster and just across the river in North Lambeth, but

none of them lived at 52 Horseferry Lane or had 5 children living with them in

the 1871 census. It transpired that William had a complicated, rather tragic, family

life which took me some time and effort to unravel.

On

census returns William Henry Harding gives 1843 as the year of his birth and

says that he was born in the parish of St Martin-in-the-Fields. His father

Henry was a coachman but I wasn’t able to trace a baptism record for him or

find out the name of his mother. In his early twenties he began a relationship

with Sophia Ann Mary Cutler. Sophia was the same age as William and like him

from Westminster, she was the second of five daughters born to Samuel and Fanny

Cutler who lived in Clarks Cottages in Causton Street, just off of the Vauxhall

Bridge Road. Sophia’s father was originally from Birmingham, a maker of

military ornaments, but her mother was another Westminster native. William and

Sophia evidently got on well, in February 1865 the pair were planning to get

married as they had the banns read by the vicar at St. John the Evangelist in

Smith Square. Perhaps the couple quarrelled because the wedding did not go

ahead. But they then must have made up as the banns were read again in

September the same year. The argumentative pair must have fallen out again because

once more the actual wedding did not take place. Whatever the cause of the

disagreement it did not keep them apart for too long; by January 1869 they were

living together in Little Chapel Street Soho and proudly having their two

daughters, Frances and Elizabeth (named after Sophia’s sister and her aunt)

baptised at Christ Church on Broadway (destroyed in the blitz and now the site

of Christ Church Gardens on Victoria Street). The following year another

daughter, Jane Mary, was baptised at St Margaret’s, the church that stands in

the shadow of Westminster Abbey. By the time of the 1871 census William and

Sophia had moved out of London and were living in Trowbridge in Wiltshire with 5-year-old

Elizabeth and 11-month-old Jane. Frances has disappeared, and has, as was all

too common in the 19th century, most likely died. And then, very unexpectedly,

the following year Sophia is admitted to Westminster workhouse taking with her

not two but five children. There are no children’s names recorded in the

workhouse records but her next of kin is given as her mother Frances Cutler of

19 Tufton Street. There had clearly been another break up with William but

where had the additional three children come from? We simply don’t know. As always

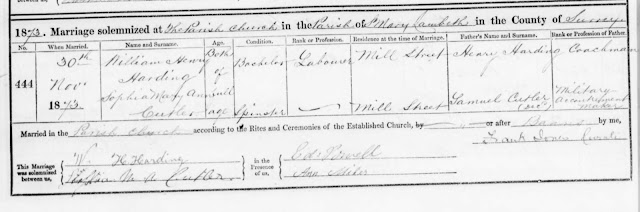

the rift between the couple was temporary and in 1873 theyr were back together

again and this time finally going through with the wedding. They were married

on 30 November 1873 at St Mary at Lambeth, the church next door to Lambeth

Palace which is now the Garden Museum. Both were living at Mill Street in

Lambeth. Almost exactly nine months to the day after the wedding Sophia and

William celebrated a double first, the birth of their first legitimate child and

first son, who was, of course, named William Henry after his father. The family

were living at 77 Berwick Street and William père was listed as a Masons

labourer. They had another son in 1877, Alfred Samuel, who seems not to have

been baptised. The family now had the 5

children mentioned in the newspaper reports of William’s death. With 5 children

and a wife to support it is no surprise that William was prepared to scale

ladders in a dark burial ground to try and rescue a parrot with a price on its

head.

|

| William and Sophia's marriage record at St Mary at Lambeth |

William’s

death was a disaster for the family; in straitened economic circumstances she

was unable to support the five children and keep the family together. On

December 21st 1879 she baptised another child at St John the Evangelist giving

her address as 23 Romney Street and declaring William to the father despite him

having died almost 18 months earlier. She told the vicar that her son, Leonard

Joseph, was born on the 21st January which, if true, would have made it

possible for William to be the posthumous father. As she did not go on to

either have any other children or to remarry or live with another man, it seems

likely that she was telling the truth and that at the time of William’s death

she was three months pregnant. The records of the Westminster workhouse tell a

sad story of increasing poverty and desperation on the part of Sophia. In

October 1878 she had been admitted to the workhouse with just her two youngest

children, two-year-old Alfred and the still unbaptised baby Leonard. The

following month Alfred and Leonard were both left separately, and alone, at the

workhouse. Whatever hardship and deprivation the family were going through

proved too much for Leonard, he died in March 1881 and like his father was

buried at Brompton Cemetery. In that year’s census Sophia was living at 19

Tufton Street, her mothers address, with Alfred. The only trace we have of the

other children at this point is Elizabeth who is listed in the census as an

inmate at the Sudbury Hall Home for Girls, on Harrow Road. In 1887 Sophia is admitted to Westminster

workhouse again this time in the company of 13-year-old William; Alfred has disappeared.

They gave their address as 10 Wood Street.

In the 1891 census when William was 15 and Sophia 48, they were living

at Lion Buildings in Tufton Street. He was working as errand boy, and his

mother as a seamstress. By June that

year Sophia was back in the workhouse, this time ominously admitted as a

lunatic. William ended up as an inmate at a boy’s home at 164 Shaftesbury

Avenue. We glimpse him again in 1894 when he admits himself to the workhouse

and we see 58-year-old Sophia on the 1901 census living at New Compton Street

and still giving her occupation as seamstress. Alfred, although apparently

given up by his mother before he was 10, was still alive in in 1902 when he

married Eliza Thelner at St John the Baptist in Great Marlborough Street but

after this, we lose sight of both him and his mother.

The

30-year-old William Henry, William and Sophia’s first son, was married on August

7 1904 to 36-year-old widow Annie Sophia Murray, living in Cleveland Street

Fitzrovia. By the time of the 1911

census the couple were living at 62 Welbourne Road in Tottenham. They had no

children and William was an out of work carman. During the first world war

William joined the Army Service Corp. His records show that he was still with

Annie and the couple had a daughter named after her grandmother, Sophia.

William died in October 1916, his death registered at Edmonton. Did little

Sophia ever know that her grandfather had died trying to save a parrot?

No comments:

Post a Comment