DEATH OF MR.

DAVID ROBERTS. On the afternoon of Friday last an elderly gentleman walking in

Berners Street fell down in fit of apoplexy. To the people who went to his

rescue he was able to utter only two words-Fitzroy Street; he never spoke

afterwards, and he died at seven o’clock on the evening of the same day. It was

a Royal Academician—David Roberts; kindly, canny Scot, well-to-do, amazingly

clever in his own sphere of art, and liked by all who knew him. (Glasgow

Saturday Post, and Paisley and Renfrewshire Reformer - Saturday 03 December

1864).

The

fatal Friday afternoon stroll would have been a short one. David Roberts had

lived at 7 Fitzroy Street since at least the late 1830’s. If he followed the

most direct route from his home he would have headed due south into Charlotte

Street ambling along for about 350 yards before turning right into Goodge

Street, then walked straight on for 150 yards or so before making a lethal left

turn into Berners Street and collapsing

somewhere along its couple of hundred yards of pavement. He had walked less

than half a mile in total; even for a man in his late sixties it wouldn’t have

been a perambulation of more than 10 minutes. The breathlessly croaked words “Fitzroy

Street” were the bathetic final utterance, his wholly unremarkable last words.

They served their purpose it seems; he was conveyed back to his home by a

gaggle of rescuers to die on the dot of 7.00pm.

“Apoplexy: A

venerable term for a stroke, a cerebrovascular accident (CVA), often associated

with loss of consciousness and paralysis of various parts of the body. The word

"apoplexy" comes from the Greek "apoplexia" meaning a

seizure, in the sense of being struck down. In Greek "plexe" is

"a stroke." The ancients believed that someone suffering a stroke (or

any sudden incapacity) had been struck down by the gods.” (medicinenet.com)

|

| David Roberts RA |

“From the late

14th to the late 19th century, apoplexy referred to any sudden death that began

with a sudden loss of consciousness, especially one in which the victim died

within a matter of seconds after losing consciousness. The word apoplexy was

sometimes used to refer to the symptom of sudden loss of consciousness immediately

preceding death. Ruptured aortic aneurysms, and even heart attacks and strokes

were referred to as apoplexy in the past, because before the advent of medical

science there was limited ability to differentiate abnormal conditions and

diseased states.” (Wikipedia)

Apart from the

interest which attaches to him an artist, and which is to be measured by the

amount of his actual achievements, there is another interest which belongs to

his career, and which is to be measured by the amount of difficulties he had to

overcome. He who began humble house-painter, and ended as Royal Academician,

has not a little to boast of. He too belongs to that proud phalanx of men whose

biographies touch most keenly all young ambition,—the self-made men who from

small beginnings have fought their way upwards to fame, to wealth, and to

station. (Glasgow Saturday Post, and Paisley and Renfrewshire Reformer -

Saturday 03 December 1864)

He

was born at Stockbridge near Edinburgh on October 24 1796, the son of a

shoemaker. His career as a housepainter began at the tender age of 10 when he

was apprenticed to Gavin Beugo, a decorator. Along with fellow apprentice and

life long friend David Ramsay Hay he studied art in the evenings. As a young

man he became a scenery painter for James Bannister’s circus on North College

Street in Edinburgh joining them on tour as a stage designer and painter at a

salary of 25 shillings a week and occasionally standing in a clown when required.

In 1817 he moved to work as assistant stage designer at the Pantheon Theatre.

When the theatre failed he was forced back into house painting. When the

opportunity arose he returned to the theatre working at the Theatre Royal in

Glasgow and Edinburgh, positions which eventually lead to offers of work in London

from the Coburg Theatre (now known as the Old Vic), the Theatre Royal in Drury

Lane and Covent Garden. Whilst working as a successful stage designer and scene

painter he began a parallel career as a fine artist exhibiting a painting of

Dryburgh Abbey at the British Institution and contributing two paintings to the

first exhibition of the Society of British Artists.

It is a fact to

be noted that David Roberts was in art wholly a self-educated man; he received

but one week's instruction, when a boy, in the "Trustees' Academy,"

Edinburgh, where he is said to have made copies of two hands. We believe indeed

that very little can be supplied to an artist by any special teaching; but in

Roberts's nature there must have been unusual vital force, or he neither could

have accomplished the immense quantity of work which we know that he performed,

nor have taken the high standing that was so readily accorded to him by his

contemporaries. (The Reader. February 1865)

While

his career was in the ascendant, his private life was descending into

catastrophe. In 1819 whilst working at the Theatre Royal in Edinburgh he had

met an actress, Margaret McLachlan, with a fine figure and blond ringlets, who

claimed to be the daughter of a gypsy and a highland clan chief. The infatuated

pair married on 3rd July 1820 and just under a year later Margaret gave birth

to their only child, Christine. He was 24, Margaret was 22. The marriage was

not happy, Margaret turned out to be a drinker and secret tippling led

eventually to chronic alcoholism. He was mortified by a wife who reeked of port

and whisky and after eleven years of marriage the situation became intolerable

to him. By now living in London he sent his wife back to Scotland in 1831. By

one of those ironies which would be viewed as contrived if it appeared in the

pages of a novel, his best friend from his days as an apprentice, David Ramsay

Hay, was also married to an alcoholic though he ‘consoled’ himself with a

mistress. On the eve of Margaret’s drunken departure for Scotland, he wrote to

Hay; “If you do not know our cases are almost parallel. Yours is not as bad as

mine, having some consolation. The state of my nerves is such I can scarcely

write. But thank God she leaves tomorrow—I hope for ever.”

But the estranged

Mrs Roberts still cast a shadow over his life. "I thank God I have had but

one grievance, but that one has been a very sad one," he wrote. In 1854,

in a bid for an increased allowance, Margaret started legal proceedings against

him, which ended in a formal separation. Roberts was angry enough to call her

"that brazen-faced monster", yet he seemed also to realise that his

own ambitions, which took him so often away from home, may have contributed to

his wife's decline. In one letter he writes: "I fear our sorrows are in

most instances of our own creating." But after Margaret's death in 1860,

he wrote of her to Hay with warmth and sadness. "I confess it, I loved her

to the last, and I have every reason to believe she knew it." (TheScotsman 08 July 2006)

The Works of the

Late Mr David Roberts. —" The Flaneur," in the Star, writes "The

late David Roberts RA left behind him 976 sketches, the originals all his great

and best known works. Amongst them are all the celebrated sketches of the Holy

Land Pictures, intended to form a gallery of these sketches for public

exhibition, as was done in the case of Mulready's sketches. Mr Roberts has also

left behind him a remarkable book of sketches, with explanatory notes attached,

forming quite a panoramic history of his life. Against the first of these is a

memorandum, to the effect that the picture was sent to the Scotch Academy and

refused, and that it was then sold to the artist's frame maker — and never paid

for. (Dundee Courier - Wednesday 14

December 1864).

|

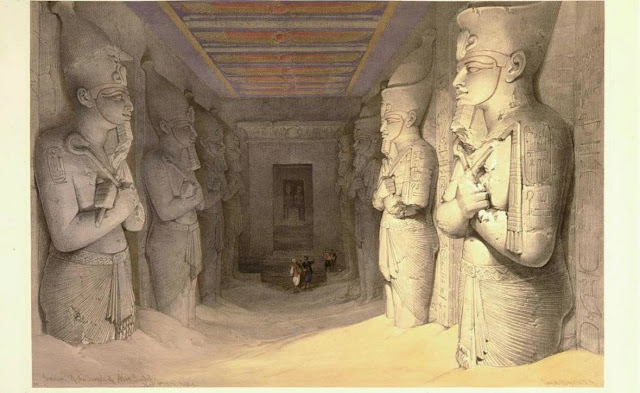

| David Roberts - Abu Simbel |

His improved

position gave him more leisure for travel, and he visited most of the countries

of Europe in search of picturesque subjects, even extending his wanderings so

far afield as Egypt and Syria. Towards the close of his life he was content to

paint the more familiar beauties of England, and almost the last work on which

he was engaged was a series of views on the Thames. He was a very popular

artist in his day, though his reputation has now suffered a not undeserved

eclipse. (Walter Armstrong, Dictionary of National Biography Vol.48 1885-1900).

He

first began to travel in 1824, visiting Normandy and producing a painting of

Rouen Cathedral which he sold for 80 guineas. He made further visits to France

and the Netherlands during the remaining years of the 1820’s. In 1832, after

sending his wife to live in Scotland, he ventured further afield, travelling to

Spain and, significantly his first taste of the East, Tangier. After J.M.W.

Turner convinced him to give up his work in the theatre and concentrate on

landscape painting he resolved to travel to the near east. In August 1838 he

set off on a long tour of Egypt, Nubia, the Sinai, the Holy Land, Jordan and

Lebanon, recording every step of the way innumerable drawings. When he returned

to England he spent seven years producing a series of lavish illustrated books

of the scenes of his travels in the orient.

|

| Abu Simbel - David Roberts |

Change is the

great monarch the universe; time, the sword of its dominion and empires, like

men, are as the dust of its feet. Change ruled over the palaces of Tyre, and

sat in the halls its desolation. Where is Gazna once the capital of a mighty

empire. Shall we ask the waters the Lake Aspbaltites where they hide the

thirteen cities of which Strabo speaks?—or make populous again the city of

Veii, which has been a solitude for nineteen hundred years. I have been led

into these passing reflections upon contemplating the remarkable "Drawings

of the Holy Land, &c, David Roberts, A.R.A.." If any productions of

this celebrated painter could have increased our estimation of his genius,

certainly the magnificent drawings we have just seen are calculated to do so.

The artist has brought to these great and momentous subjects a mind of equal

grasp, a nobility of conception, and a vastness of execution absolutely

wonderful. It is truly wonderful; it is truly surprising, how, the space of a

few inches, he has been able to impress the spectator with a feeling of

immensity, with a perfect appreciation the colossal order of the architecture;

indeed, the columns, entablatures, pilasters, and inscriptions, seem upon so

stupendous a scale, that might almost fancy that we hear the architect, in the

golden fame of his triumphs, boastfully-asserting, " Other men build for a

day; I build for eternity." Alas! the columns still survive; but they

ungratefully conceal the name of their founder. (Yorkshire Gazette - Saturday

24 October 1840)

He was a very

happy man. This must have been evident to all who had any acquaintance with

him, for his genial temper manifested itself in his face, and his voice, and

the mirth of his conversation. He had the enjoyment which belongs to the

inclination and habit of industry, without the drawback of the stiffness, and

narrowness, and restlessness which too often attend it. In the last autumn of

his life, when he was absent from his regular work, and staying at Bonchurch

with his daughter and son-in-law and their family, he occupied himself with

cleaning and renovating his old sketches, conversing gaily all the while. His

health was good; his fame was rising, as appeared by the constantly increasing

prices given for his works; he was blessed in family affection, and rich in

friends. He was passing into old age as happily as possible when he was struck

down by a death which spared him the suffering of illness, infirmity, and

decline. On the 25th ult. he went out from his own house in apparent health,

and cheerful as usual. As our readers know, he staggered and fell in the

street, and died at seven the same evening…. David Roberts,

the Royal Academician, will be regretted far and near, and his death recorded

as one of the grave losses of a grave year. (London Daily News - Thursday 01

December 1864)

David, I am researching David Roberts family tree, and I am interested in connecting with any members who are up to it. Please let me know if you have any contacts.

ReplyDeleteThanks

Sunil

sunshinde at hotmail.com

Hi Sunil, sorry I don't have genealogical contacts for descendants of David Roberts. Good luck in your research.

DeleteThank you David.

ReplyDelete