“Three soldiers of the Coldstream Guards were walking in Montgomery street. Onegavean opinion in which all concurred. It was the woman, they said; he showed himself a man afterwards.” James Joyce ‘Finnegans Wake’

At

around midnight on Tuesday the 3rd October 1922, a married couple Percy and

Edith Thompson were walking back to their house on Kensington Gardens from

Ilford train station. They had spent the evening in London at the Criterion

theatre watching a Ben Travers farce The Dippers. As the couple strolled home

arm in arm they were followed by twenty-one-year merchant seaman Frederick

Bywaters. In Belgrave Road, less than 200 hundred yards from their house,

Bywaters pulled a twelve-inch knife from his coat, broke into a run and,

catching up with the Thompsons, stabbed Percy twelve times in a short, frantic

and fatal attack. Most of Percy

Thompson’s wounds were superficial but there were three severe neck wounds, one

of which severed the carotid artery, sliced open the oesophagus and flooded his

stomach with blood. The scuffle was over

in less than a minute. Frederick Bywaters immediately fled the scene leaving

Percy Thompson to bleed to death in the arms of his hysterical wife.

|

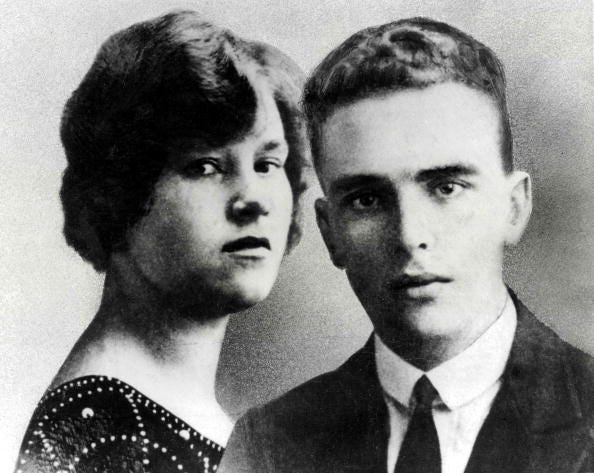

| Edith Thompson & Frederick Bywaters |

Edith

Graydon was born on the 25th December 1893, the eldest of 5 children, in

Stamford Hill in North London. When she was 6 the family moved out their

cramped accommodation to a house in Shakespeare Crescent in the new suburb of

Manor Park in East London. When Edith

was eight, Frederick Bywaters was born round the corner in Rectory Road,

E12. The two families grew up together

and Frederick became a great friend of one of Edith’s younger brothers. Of

course, she would have paid no attention to a small boy 8 years her

junior. Edith left school at 15 and held

a variety of jobs in shops and offices until, in 1911, she found work at the fashionable

wholesale milliners Carlton & Prior in the Barbican, where she was to

remain, a valued and trusted employee, until her death. She met the 19-year-old

Percy Thompson a few months after leaving school, shortly before her sixteenth

birthday.

Edith’s

relationship with the stolid Percy was ambivalent almost from the start. They

shared many mutual interests, in music and the theatre and in amateur dramatics

but Edith was far livelier and more adventurous. Whilst Percy was a plodder at

work and never received promotion, Edith quickly rose from a relatively menial

sales job to assistant buyer, acquired passable French and went on sales trips

to Paris. But she stuck with Percy, eventually losing her virginity to him on a

holiday in Ilfracombe and thereby making it almost a certainty that she would

have to marry him. After a six-year long

courtship (incredibly long for the time and quite probably a reflection of her

uncertainty about a lifelong commitment to him) the couple finally married in

1916. Shortly afterwards, with the

ignominious threat of conscription hanging over him, Percy enlisted in the

army. Within 4 months he had wrangled himself an honourable discharge with

‘suspected’ heart trouble (rumour had it that he had taken to smoking 50 cigarettes

a day to induce cardiac palpitations).

Percy’s

cowardice contrasted poorly with the much younger Frederick Bywaters eagerness

to involve himself in the fight for King and country. By 1917, and still only

fifteen he was still too young to enlist in the armed forces. Instead, he spent

the spring and summer trying to volunteer for the merchant navy convoys that

were being regularly torpedoed by German U boats. His mother blocked his first

successful attempt to sign on by withholding parental permission. Frederick simply lied about his age on his

next attempt and in February 1918, after signing a disclaimer that he was

accepting a position in the full knowledge of the dangers faced by shipping in

war time, he set sail for India in the P & O troop carrier Nellore. For the

next three months his mother had no idea where he was. His next voyage was to

China. When the war ended Frederick decided to stick with the merchant navy.

Following the death of his father from injuries sustained in a gas attack on

the Somme, his mother had been forced to sell the house in Rectory Road and buy

somewhere cheaper in South London. When Fredrick returned from a trip to China

and Japan in early 1920 his family were settled in Upper Norwood. His ship was

berthed in East Tilbury, and knowing that he was looking for temporary lodgings

somewhere closer to Tilbury than Norwood the Graydon’s suggested he take a

spare room at Shakespeare Crescent. It was here that he and Edith met again for

the first time since Frederick had been a small boy. For the next seven weeks

Frederick met regularly with the Thompson’s at Percy’s in-laws. The two men

struck up friendship and Frederick began to take an interest in Edith’s younger

sister Avis. After seven weeks he rejoined his ship on a voyage to Bombay and

was away from the country for several months.

|

| Frederick, Edith and Percy in the back garden in Ilford |

In the summer of 1921 Frederick was back in the country and staying once again with the Graydon’s in Manor Park. The Thompson’s were planning a holiday on the isle of Wight and Edith had insisted on inviting her younger sister Avis. When Frederick showed up Percy fatefully suggested that he join them on the holiday as a foursome would be much more fun than Avis tagging along on her own. Percy was very aware that Avis was infatuated with the handsome young sailor and he seemed determined to play the matchmaker. In fact, it was during this week on the Isle of Wight that Frederick and Edith first made their mutual interest in each other clear, at least to each other if not to Percy and Avis. The holiday was such a success that Percy invited Frederick to come and lodge with him and Edith at their new house in Kensington Gardens in Ilford.

Within

a few days of moving into the Thompson’s home Frederick and Edith became

lovers. On the 27th June, Frederick’s 19th birthday, they had the house to

themselves as Edith had a day’s leave from her job. As soon as Percy left for

work Edith made breakfast for the birthday boy and took it up to his bedroom

where she inevitably ended up joining him in bed. Opportunities for sexual encounters

would have been limited but the lovers took them whenever they could. Over the

following weeks Percy became increasingly suspicious about the relationship

between his wife and their young lodger. Freddy showed no desire to find

himself a new berth on a ship and lost his former interest in passing boozy

nights in local pubs with his host. Instead, he hung aimlessly around the house

waiting to dance attendance on Edith when she returned home from work, helping

her to set the table for meals, drying the dishes she had washed, and generally

fetching and carrying for her. Edith was bright and cheerful with Freddy but

irritable and impatient in her husband’s company. Most ominously she shunned

his physical attentions. Percy began to grow sullen and resentful. Things came

to a head on the August bank holiday. The three were sitting in the back garden,

Edith sewing, Freddy reading a book, Percy the newspaper when Edith asks her

husband to go into the house and get a pin for her. When he doesn’t jump up,

Freddy does and disappears into the house. A furious argument breaks out

between husband a wife. It lapses when Freddy reappears but starts again later

inside the house. Freddy discretely steps outside to avoid being drawn into the

squabble but as soon as he is gone Percy breaks into a tirade about Edith, her

sister and her family in general. Goaded Edith screams back and Percy slaps her

several times and pushes her backwards into a table. Hearing the fracas Freddy

comes racing in back inside and steps between the Thompsons. Edith rushes

upstairs but when Percy tries to follow Freddy stop-s him. There is no physical

fight, Percy is a coward. He orders Freddy out of the house but Freddy refuses

to go and tells Percy that if he ever touches his wife again, he will have him

to deal with.

The

relationship between Edith and Freddy is now more or less out in the open as

far as Percy is concerned. When Percy continues to insist Freddy moves out, in

the end he has to comply. With no income he is also forced to go back to sea.

While Freddy is away Edith begins the correspondence with him that would

eventually get her hanged. The couple’s clandestine relationship continues whenever

Freddy is in the country but when he is away Edith writes to him in candid

detail of her daily life. She writes of her visits to the theatre, her flutter

on the Derby, and a dinner with a mysterious man from Ilford called Mel, who

has realised that Edith is having a sexual relationship with Freddy and

therefore thinks it is worthwhile chancing his arm while the sailor is away. She

writes of Percy’s sexual advances, her refusal to succumb to them and her

husbands plaintive whine “Why aren’t you happy with me? We used to be happy.”

She holds Percy’s advances off until 5th December; two days later Edith is

putting an abortifacient into her porridge in case the encounter leads to a

pregnancy. Percy picks up the wrong bowl and eats the drugged porridge himself.

This semi farcical episode provides the germ for a series of recurrent

fantasies in which Edith imagines drugging Percy’s tea or mixing ground glass into

his porridge. She shares the details of her periods with Freddy, and tells him

about is either a miscarriage or a self-administered abortion. The letters have

the virtue of honesty, it was this quality of course which so shocked the judge

and jury at her trial. What sort of woman would openly discuss her sexual

feelings and her periods with a man? It was this unseemly candour which

led to Edith, the Ilford milliner, being compared to Messalina, the whorish

wife of the emperor Claudius who famously challenged Scylla, Rome’s premier prostitute,

to a contest to see who could satisfy most men in a single night.

During the following year Freddy tries to get Edith away from Percy, even going to see him after the husband spots his wife and her ‘sailor boy’ at Ilford Station together. In the row that follows Percy tells Edith that if Bywaters were a man he would his permission to take out his wife. Edith relays this to Freddy who calls at Kensington Gardens to have things out man to man with Percy. He tells Percy that he doesn’t need anyone’s permission to take Edith and suggests that the couple come to an amicable agreement, a separation or a divorce. The humiliated Percy salvages what little dignity he can by digging in his heels and telling Freddy “Well I have got her and will keep her.” The argument between the two men does on for the best part of two hours but Percy refuses to budge although he finally agrees not to hit his wife anymore. All three parties no doubt grew increasingly frustrated until a desperate Freddy decides that there is only one way to resolve the situation; Percy must die. At the couple’s trial Freddy insisted that he had acted alone and that Edith had nothing to do with the murder of her husband. But from those letters the prosecution built a case that Edith, who was 29 and 7 years older than the 21-year-old Freddy, had manipulated, sexually and emotionally, the infatuated younger man. Her letters proved how shameless she was, they proved how she plotted to poison her husband or to kill him with ground glass and when that failed, how she insinuated to the hapless Freddy that he should kill Percy for her, so that they could finally be together. The evidence against Edith was scanty to say the least and one would hope that no modern jury would convict her on the basis of it.

Justice

was much swifter in the 1920’s than it is today. By the 6th December 1922 Frederick

Bywaters and Edith Thompson were both on trial for murder at the Old

Bailey. On the 9th January 1923, little

more than 3 months after the murder Bywaters was executed at Pentonville Prison

and Thompson at Holloway. The trial and

execution generated a remarkable amount of public interest. People queued from

midnight in an unusually cold winter to ensure a place in the public gallery at

the court and the newspapers devoted dozens of pages of close print to the

affair. The leader writer of The Times was at a loss to understand the

attention given to a ‘simple and sordid case’ by the British public in ‘a trial

which presented really no features of romance and which provided none of the

horrors that appeal to a morbid mind.’ He went on to concede that there were

elements of the crime passionnel, ‘but that extenuating term has never

received a welcome in this country.’ No

welcome from the legal establishment perhaps but from the British public it was

another matter. Within a matter of days of the verdict prurience had turned to

pity and public opinion swung firmly behind the condemned couple (though it was

Bywaters that initially attracted the lion’s share of sympathy). The Daily Sketch ran a campaign to save the

pair from the hangman. On the day following the launch of the campaign the

newspaper received 10,000 letters of support in the first post and a long queue

to sign a petition had formed by midmorning from the lobby of its offices, out

into the street and then 500 yards along the pavements. The magistrate who had

committed Bywaters to trial wrote to the Home Office pleading for the boy’s

life. He was followed by dozens of other worthies as the campaign gathered

pace. Eventually the Daily Sketch collected over a million signatures in

support of a reprieve, the largest ever petition in support of a condemned

prisoner.

The

82-year-old Thomas Hardy, who had read Edith Thompson’s correspondence and was

struck by her looks, produced the distinctly unsympathetic poem ‘On the

Portrait of a Woman about to be Hanged’ when he learned that she was to be

executed. In Paris James Joyce followed

the case closely in the British newspapers and interpolated several passages

from them into his notes for Finnegans Wake.

In the years that followed the case continued to exert a fascination

that has never gone away. A score of novels, influenced to some degree by the

case, appeared over the next 20 years including Dorothy L. Sayers ‘The

Documents In The Case,’ E.M. Delafield’s ‘The Messalina Of The Suburbs’ and F.

Tennyson Jesse’s ‘A Pin To See The Peepshow.’

The case was covered in the Notable British Trials series, Alfred

Hitchcock later toyed with the idea of basing a film on it and by the time

George Orwell came to write ‘The Decline of the English Murder’ for the Tribune

in 1946 he could cite it as a classic example of the great British murder perpetrated,

it seemed, purely for the delectation of the readers of the News of the

World. Following the Second World War,

Orwell notwithstanding, Thompson and Bywaters seem to largely disappear from

public consciousness (though the poet Kathleen Raine who was 13 at the time of the

trial and living in Ilford, could declare in her 1974 autobiography that ‘Edith

Thompson c’est moi’). Curiosity about domestic murders was gradually being

replaced by an obsession with the phenomenon of serial killers. In the last thirty

years however there has been a revival of interest beginning with the

publication of Rene Weis’s account of the affair, ‘Criminal Justice’ in 1988.

PD James’ discussed the case at length in 1994’s ‘The Murder Room’, the same

year that Shelagh Stephenson’s radio play ‘Darling Peidi’ was broadcast. Since

then Jill Dawson published the well-received novel ‘fred & edie’, and a

feature film ‘Another Life’ dramatising the events that led up to the murder

was released in 2001. There have been further books, notably by Laura Thompson

and Edith’s letters have also been published in full.

Following her execution Edith was buried in an unmarked grave within the grounds of Holloway Prison. Her parents expressed a wish for her to be buried with them but this was not possible for an executed prisoner. In 1971 the prison was redeveloped and the 5 bodies of executed women (including Rith Ellis) were exhumed. Ruth Ellis was buried elsewhere but the families of the other four executed women were not informed. Edith and the three other women were moved in secret and reinterred at Brookwood Cemetery. Since 2000 Edith’s family and the author Rene Weiss campaigned to have her body moved from Brookwood to her parent’s grave in the City of London cemetery. On Tuesday 20th November 2018 Edith was exhumed from Brookwood and taken by private ambulance to an undertakers in Kingston. On the 22nd her body was brought to the City of London cemetery where a memorial service was held in the Anglican Chapel before Edith was reburied in her parent’s grave.

.jpg)

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment