The

Wellcome Collection has a heavily annotated copy of this (in)famous photograph

of Major General Horatio Gordon Robley seated before his collection of 33 mokomokai,

Māori preserved heads. Its provenance is Stevens

Auction Rooms formerly of 38 King Street, Covent Garden. One note says that this

is a “1895 photograph”; this copy was presumably given by Robley to Henry

Stevens the auctioneer when he attempted to sell Robley’s mokomokai collection in the

1900’s. It was probably Stevens, or one of his staff, who made the notes on the backing sheet, jotting

down details from Robley’s verbal description of his collection, to be used as

sales patter during the auction. “Note the 15th 14th head has its portrait in oils {Collection Donne”; the painting

of this particular head, probably done by Robley himself, he was a talented artist, must have been in

the collection of Thomas Edward Donne (1860–1945) one time Trade and

Immigration Commissioner at the New Zealand High Commission in London, an acquaintance of Robley's and a well known collector

of Māori antiquities. “This collection increased to 35 specimens,” Steven's notes but only 33 are

shown in the photo, “offered to N.Z.d for years. Visited by Maoris over for

coronations of King Edward and King George, also Victoria's Jubilee.” Robley had indeed offered his collection to

the Government of New Zealand for the sum of £1,100 but his overtures fell on deaf

ears, the colonial government wanted nothing to do with preserved Māori heads and in 1907 the collection eventually went, in toto, to the American Museum of Natural

History for £1,250. At the bottom left

of the photo, beneath the two smallest heads, another note reads “child and boy

preserved by friends”. In the Oxford D.N.B. article on the Steven’s family Michael

Cooper says that "the most gruesome offerings,” at the auction house, “were

shrunken human heads, sold by Stevens on several occasions, the most remarkable

being, in 1902, the collection of thirty-three tattooed Maori heads, the

property of General Robley, who, it is said, decorated his bedroom wall with

these relics and 'when unable to sleep at night would rise and comb his Maoris'

hair, and felt himself soothed'”. Robley

was not averse to exploiting the shock value of his collection of heads to

startle his contemporaries but even he might have balked at the unsettling

image of the insomniac rising in the small hours to soothe himself by combing

the locks of decapitated corpses. Surely there is no truth in this?

|

| Robley in his early twenties, in full dress uniform |

Robley

was born in Funchal on the Portuguese island of Madeira in 1840. His father was

a retired infantry captain in the Madras army of the East India Company. His

mother, the daughter of English residents of the island, was enough of an accomplished artist

to have a book of her drawings and watercolours of Madeiran flora published in

London. Robley inherited his father’s military bent and his mother’s artistic

one; at the age of 18 his parents put up £450 for their son to purchase the rank

of Ensign in the 68th (Durham) Regiment of Foot (Light Infantry). After training

in Ireland he was sent to Burma to join his regiment. It was here that he first

demonstrated an interest in other cultures; he learned Burmese, took to

sketching daily life in the countryside and allowed Buddhist monks to tattoo a

red Buddha on his right arm. In 1861,

after a period of leave in England, he was posted to India where he took command

of the guard assigned to watch over the last Mughal Emperor of India, Bahadur

Shah Zafar, held in captivity in Rangoon until his death in 1862. Robley produced

a watercolour sketch of the Emperor in his last days, sitting cross legged on a

bed made of rough timber, looking rather down at heel and smoking a hookah. In 1863 his regiment was sent to New Zealand

to help quell the Māori rebellions against British rule. Robley bought a Māori vocabulary

and other books about the native New Zealanders and apparently found an irresistible

fascination in the culture of the people he was there to fight. He sketched and

painted during the entire period of his posting in North Island. He was particularly

drawn to Māori tattoo designs and produced dozens of detailed paintings from

the dead and wounded on the battlefield and of prisoners of war. He also began

a relationship with a Māori woman, Herete Mauao, with whom he had a son, Hamiora

Tu Ropere.

|

| Robley's watercolour sketch of Bahadur Shah Zafar |

In 1866 his regiment was sent back to England where he remained for the next 14 years. He purchased the rank of Captain in 1870 and a year later was transferred to the 91st Regiment (Princess Louise's Argyllshire Highlanders). In the 1880’s he served in South Africa and Ceylon, was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel and in 1887, he retired with the honorary rank of Major General. It was now that he began to devote himself in earnest to collecting and studying mokomokai. Robley came late to the collecting scene – it had been at his height in the 1820’s and 30’s before the Sydney Act, passed in 1831, prohibited the exportation of heads from Australasia and effectively put an end to the worst excesses as described in an article on Robley’s collection published in The Graphic in 1896;

It

was natural enough that a head upon which so much skill had been expended [in

tattooing] was deemed too precious a work of art to be buried. So arose the

practice of Mokomokai. When a man with a good head was killed or died his head

was cut off and baked in an oven. When done to a turn, it was put away in

cloths to be on produced on festive occasions by his relatives. In the case of

an enemy, the body was eaten and the head was, after being baked, mounted on a

pole as a kind of trophy. Presently white men began to trade with the Maoris,

and then a brisk traffic began in these dried heads, which were worth some £40

or £50 in the market. The natives received in exchange guns and powder. Very

soon the demand for fine heads became so large that no man with well tattooed

features was safe, and Moko naturally became unpopular. So keen indeed, became

the trade in heads that chiefs used to have their best. looking slaves

tattooed, carry them on board a ship, and offer to sell any one of them. The

illustration which we publish this week of the sale of a living head represents

no imaginary scene, but one that really occurred some 70 years ago. A Maori

chief, on finding that the dried head of a native which he had brought on board

a ship for sale, was objected to by the intending purchaser as a poor sample of

Mokomokai, allowed the force of the argument, but, being desirous of doing

business, pointed to a number of his slaves, whom he had brought with him, and

said "Choose which of these heads you like best. When you come back, I

will take care to have it dried and ready for your acceptance.” The traffic in

heads was suppressed in 1831 by law, and the art of Moko is rapidly dying out.

|

| "Bargaining for a head, on the shore, the chief running up the price" – sketch by H. G. Robley |

Robley’s

first head was bought to rescue it from being used as an advertisement; he

later wrote that when he was “passing one day along the Brompton Road, I espied

from the top of an omnibus on which I was travelling a phrenologist

re-arranging his window, & in the window was a Māori head placed there to

such base use as an advertisement to the cranium part of the human frame for

the purpose of attracting attention to his doctrine.” Robley got off the bus at

the first stop and managed to convince the phrenologist, Stackpool Edward O'Dell, to sell him the head. He later described the trade in Māori heads as “gruesome”, “replete with abominations” and

said that it was “repulsive to [Māori] instincts and which they only adopted as

a desperate measure to preserve their tribes from annihilation.” But his abhorrence

at the trade did not stop him building up what was an extremely large

collection, much larger than those owned by many museums as Robley was quick to

point out to the press. The Westminster Gazette reported in 1900 that “Major-General

G. H. Robley, the famous head-hunter” had, at that point, “a grand total of

twenty-six heads in the collection. The British Museum has four similar heads;

the Jardin des Plantes, Paris, six; the Museum, Berlin, two; the Museum,

Vienna, one; the Museum, Rome, one; Smithsonian Institute, Washington, U.S.A.,

one; and the Museums of New Zealand, four…” He was not shy of publicity of

drawing attention to himself or his collection. In his memoirs he describes

what happened after a successful bid at an auction for “a head from the private

collection of the late Dr. Paterson Bridge of Allan — as soon as it became

mine, to the astonishment of the saleroom bidders, I hongied, explaining the

rubbing of noses was the correct greeting.” On another occasion he took a head

out to dinner with him; “I remember when Seddon gave a cold meat banquet at the

Holborn [restaurant] and I took a head with me – many of the young men were

astonished at my lecture on it.” A visitor to his flat in St Alban’s Place, in the Haymarket, later wrote that “on my first visit to London in 1905 I

called on Major General Robley and found him taking his ease at full length on

a couch; around the somewhat small room were displayed 38 … preserved head with

tattooed faces — they were on tables, sideboards, mantle-piece —everywhere. The

possessor of them was smiling proudly at the gruesome display…” Despite this

clowning Robley wanted to be taken very seriously; he published two books on Māori

culture, ‘Moko or Maori Tattooing’ in 1896 and ‘Pounamu: Notes on New Zealand

Greenstone’ in 1915. In August 1902 he wrote to the Evening standard about a visit

to his collection from the Māoris who were attending Edward VII’s coronation;

The Maori Coronation Contingent who have left for Aldershot, and who return to New Zealand on September 6, came to see my collection, in which were the valued preserved heads of Chiefs fallen long ago in native battles (33), and were gratified with the care bestowed on their guarding. It was an honour in old times to preserve the heads. It was their opinion that these valued relics should be returned to New Zealand, rather than run the risk of being scattered. The Museums of that country happen to be very poor in specimens, having only four, and, in fact, New Zealand has been depleted of its historic relics by the agents and friends of the world’s Museums, leaving but little comparatively.

|

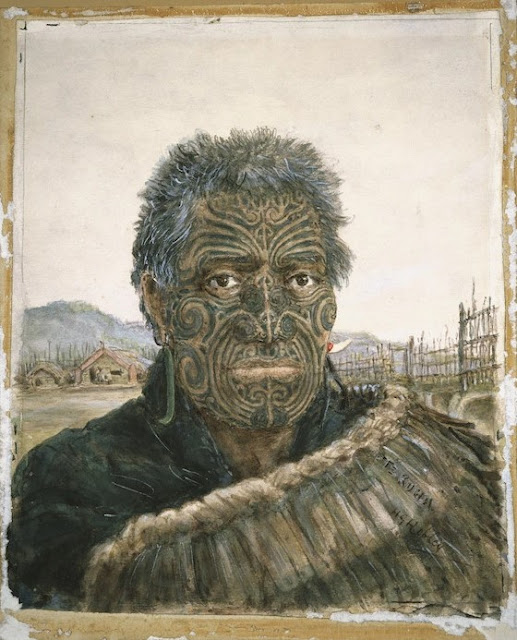

| Head and shoulders portrait of Te Kuka. July, 1864 by Robley |

Robley’s

collection was acquired by the American Museum of Natural History in 1907. The decision

to sell was prompted by his increasingly poor health and the debts he had accumulated

whilst building up the collection. Unmarried and with his family living abroad the

67-year-old Robley had to consider how he was going to take care of himself in

his final years. These were spent in a nursing home in the Peckham Road in Camberwell

where he died at the age of 90 on the 29th of October 1930. Although he was not

forgotten, many newspapers ran his obituary in the days following his death, he

had no close family in England and seemingly no financial resources. He was

buried in a common grave in Streatham Park Cemetery and no memorial was ever

raised to his memory. The American Museum of Natural History held on to his

collection of mokomakai until 2014 when they were returned to New Zealand as

part of the largest repatriation of ancestral remains ever carried out. In New

Zealand, Robley’s Māori descendants were ambivalent about their ancestor; his

great granddaughter Googie Tapsell is in her 80’s and told Radio New Zealand

that her Uncle Hepata “hated his grandfather, didn’t want to know about him…

hated him.” When he was given a copy of Robley’s book on Mioko “he stomped on

that book … he said ‘I don’t want to know about him’.” Her own mother, Robley's

granddaughter, kept up a connection to him through letters to London; “Mum

loved him. He wanted to bring her to England for her education … But she

wouldn’t go. Didn’t want to leave New Zealand.” In 2017 Tim Walker, a senior

curator at Te Papa, the National Museum of New Zealand, tried to raise funds

and obtain permission to erect a headstone over Robley’s grave in Streatham Park

but his efforts seem to have come to nothing and the grave remains unmarked.

.jpg)