The

only place I visited at this years Open House event was the crypt of St Mary’s in Wanstead. Our guide for the short tour was Sian Paterson who was

knowledgeable and funny and made sure that we didn’t brain ourselves on the pipe

for the water mains that cuts across the entrance tunnel as we descended. The foundation

stone of St Mary’s was laid in 1787; the crypt must have been completed before work

started on the main body of the church. It runs the entire length of the building,

about 25 metres, with an additional 10 metre entrance tunnel leading from the

churchyard. Inside there are, I think, 15 vaults running either side of the

main passage, the odd number being presumably being because the vault housing

members of the Child family (including the Earl’s Tylney) must be considerably

larger than standard. A vault originally cost £105 for a parishioner and £125

if you were from outside the parish boundaries. That would have been quite a

hefty sum in the early 1800’s but each vault has space for several coffins and

I would imagine the lease is in perpetuity so in theory the occupants can rest

undisturbed until the last trump. The crypt is constructed in red brick with

stone imposts on the pillars on which often sit candle stubs left over from the

times when families still came to visit or left by the bricklayers when they

bricked up the vaults. Vault walls have ventilation holes large enough to view

the coffins inside and Sian showed us how to shine the torch from your mobile

through one hole while you viewed the interior through another.

A

portion of the bricked-up entrance to one vault has been knocked down at some

unknown point in the past and the coffins disturbed. It was originally thought

that this had happened in the 1950’s and that the perpetrators were intending

to steal the lead linings of the coffins. You can clearly see that the lead has

been cut and peeled back, some seems to have been removed but some large pieces

are still in place, peeled back as though to allow access to the inner coffin.

A visitor to a previous Open House in the crypt told Sian that he had been in

the church choir in the 1950’s and it was a rite of passage for new choirboys

to be taken down to the vaults and dropped over the broken wall to stand next to

the coffin! He also told that her that the vault had been broken into long

before then. Some locals like to think that perhaps body snatchers had been at

work; the date on the vault is MDCCLXXXVIII (1788) which is the right timeframe

for resurrectionists (and shows that the vaults were being used while the church

was still being built) but why would the vault have been left open? The robbery

must have taken place at a later date. If the robbers were after lead why did

they leave so much of it? Maybe they were looking for jewellery left on the

corpse? Who knows – maybe someone other than a petrified choirboy needs to get

inside the vault and check.

There are several vicars buried in the vaults and at least a couple of Lord Mayors. Sian introduced us to Sir William Curtis, affectionately known as ‘Billy Biscuits’ and who is described in the History of Parliament as "a portly and bottlenosed bon vivant". Sir William was born in Wapping in 1752, the son of a sea biscuit manufacturer. In time the family business extended to ship owning and their vessels carried convicts to Australia and engaged in whaling in the South Seas. Sir William owned a large house called Cullands Grove near Southgate and was famous for the lavish banquets he hosted there, George IV sometimes attended them. In time he became an MP, served as Lord Mayor of London and was created 1st Baronet of Cullands Grove in 1802 by George III. He died in Ramsgate in 1829; on the day his body was removed from his residence Cliff House, the large funeral set out through a town in which the shops “were closed ; minute guns were fired from the yacht till the return of the Procession; and although the weather was wet and stormy, every one appeared eager to pay this last tribute of affection and respect to departed excellence” according to the London Evening Standard of 27 January. “The party accompanied the funeral to the second Milestone beyond the town of Ramsgate. The body will remain the first night at Sittingbourne, the second at Dartford, and will pass through London on Wednesday on its way to Wanstead” the newspaper added.

SIR

WILLIAM CURTIS's WILL The will of the deceased worthy Baronet having been duly

proved, and administration granted, in the distribution of extensive property,

real and personal, we find the following items:—

Item.

I bequeath my physic to the dogs; remainder in fee to the physicians who

attended me, in recompense for their singular sagacity, in discovering that "my

last disease was mortal." The gally-pots I leave to Lady Sefton, who is

admirer of porcelain; and as Lord Deerhurst is a patron of boxes he is welcome

to those that held pills and boluses.

Item.

To Mr. Michael Angelo Taylor, I leave my handsome footman, who is a capital

plate cleaner, as he used regularly to swab the dishes on board my yacht. He

has no objection to any work he may be put to; and is remarkably light in his

ascents and descents the back stairs. He will have only look to his livery—and

he will be answerable for his breeches and stockings.

Item.

To Mr. Brougham, my courage, being a JUDGE in that matter.

Item.

To the Duchess of Saint Albans, my charity; with the injunction that she shall

not spend more than fifteen shillings in advertising every five given, in consequence

of its impulse.

Item.

To Rowland Stephenson, my activity, a reward for his honesty, in not stopping,

when his partners did.

Item.

To the Commissioners of Customs for Ireland, for the signal service which they

did to merchantmen, in permitting my pleasure yacht to have the first entrance

into new docks Dublin, whereby she became free in her moorings, with divers

other advantages, too numerous mention, I bequeath one penny per man, to

purchase salt to their potatoes.

|

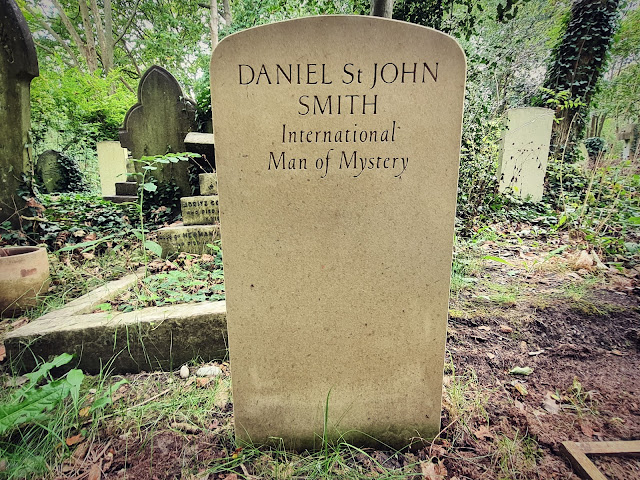

| The entrance to the Childs/Tylney vault - the heart of the 2nd Earl Tylney, John Child,still sits outside the vault in the glass bottle it was shipped in from Florence. |