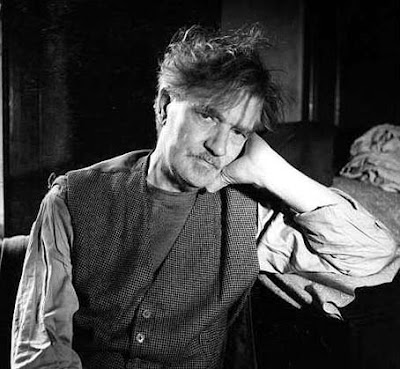

Artist

Who Refused to Paint Hitler Mr. Austin Osman Spare, an artist who refused

a commission from Hitler in 1938 to paint a portrait of the dictator, and who

had a painting hung in the Royal Academy when he was only 17, died yesterday in

a London hospital, aged 69. In the blitz his studio was bombed and his right

arm badly injured. After several years of poverty and struggle he regained the

use of his arm and last year exhibited again in a Paddington gallery.

Birmingham

Daily Post - Wednesday 16 May 1956

In

a rather commonplace grave that lies almost at the dead centre of an

unremarkable suburban cemetery are buried the mortal remains of the

extraordinary Austin Osman Spare, a working class artist and visionary cast in

the same mould as William Blake. Like Blake Spare lived on the fringes of

society, gathering some renown for his drawings and paintings but often the

target of ridicule for his esoteric beliefs and his refusal to conform to the

norms of polite society. He was buried anonymously in Buckingham Road cemetery

in Ilford, interred in his father’s grave. There is no mention of Spare on his

father’s plain granite kerb memorial and nothing to mark out the grave site

amongst the almost uniformly grey ranks of toppled headstones and grave

markers. But when I visited someone had managed to locate this needle in a

haystack before me, in fact a small delegation seemed to have made its way to

the grave sometime in the previous days or weeks and left a greetings card, a bundle

of desiccated twigs that may possibly have been red carnations when they were

originally purchased, and a still unopened miniature bottle of Tomintoul 10

year aged single malt whisky. “I hope

you’ll enjoy these humble gifts,” said Mia in a message in the card. “Dear

Spare,” said Zak, “thank you for imagining a system of magic I could engage

with in good faith.” The message from the leader of this trio of young devotees

of the Zos Kia Cultus, who signs himself off with a sigil, was unfortunately almost

completely illegible apart from the final few words “continue to work your

magic in the 21st century.” I would like to imagine these three callow

occultists conducting some sort of necromantic midnight rite at the graveside

but, given how hard it is to find,it seems unlikely that they would have been

able to locate it in the dark. They probably arrived on the 25 bus in the late

afternoon, spent at least 40 minutes wandering from grave to grave reading

inscriptions and epitaphs until they found Philip Newton’s, then dropped a

sorry bunch of carnations bought from a garage and the miniature whisky filched

from one of their parents onto the tomb before gathering in a semi circle and

self consciously mumbling some Thelemite orison. Spare would have been pleased to be remembered;

of the hundreds of thousands of graves in London’s cemeteries only a tiny

fraction draw total strangers to them to pay homage to their occupants decades

after their death and even fewer receive grave gifts.

Philip

Newton Spare, Austin’s father, was born in Pickering, North Yorkshire in 1857

and came to London as a young man to lodge in Grays Inn Passage, Holborn and to

join the Metropolitan Police. His mother, Eliza Osman, whom he never got on

with, was originally from Farringdon Gurney in Somerset and married his father

at St Bride’s in Fleet Street in 1879. Spare père remained a police constable

for his entire working life, based at Snow Hill station in the city. He seems

to have had an unusually dull career; the only mention of him in the papers

came in January 1911 when he had arrested Joseph Scott a labourer for being

drunk and disorderly. At Mansion House Police Court Police Constable Spare has

explained to the Lord Mayor that he had been at the foot of the boat pier at

Blackfriars at 10.00pm the previous Sunday when he had seen Scott coming up the

steps from the river stark naked. Apparently the rather foolhardy Scott had

accepted a half crown bet and jumped naked from Blackfriars Bridge into the

river, in January, in the dark. He was let off with a caution. Philip and Eliza started married life in police

lodgings in Snow Hill, near Smithfield meat market. Austin was the fourth of

the Spare’s five children.

In

1894, when Austin was 7 years old, the family moved to Kennington. Austin soon

began to show precocious talent as an artist and when he left school at the age

of 13 he was apprenticed to Sir Joseph Causton and Sons, a firm that designed and

produced posters. In the evening he studied at Lambeth School of Art. In 1904

Philip sent two of Austin’s drawings to the Royal Academy:

BOY

ARTIST HONOURED - EX-POLICEMAN'S SON EXHIBITS AT THE ACADEMY

The Royal Academy

exhibition was opened on Monday. The youngest exhibitor this year, as stated in

last Thursday's Daily Mail is only seventeen years old. His name is Austin 0.

Spare and he is the son of Mr. Philip Spare, until recently a constable in the

City of London Police Force. He sent two black and white drawings to the

Academy, says the Central News, both of which were accepted, one being hung.

They were executed when the artist was sixteen years of age. Spare was born in

December 1887. He was educated at St. Sepulchre's School. Snow Hill, and St.

Agnes School, Kennington Park and received his first art training at the

Lambeth Evening Art School under Mr. Macady. There, before he was twelve, he

took three first class certificates. At the age of fourteen he won a £10 County

Council scholarship and one of his drawings was selected for the British art

section at the Paris International Exhibition. When he was fifteen some work

which he was doing for Messrs. Powell, the stained glass manufacturers,

attracted the attention of Sir William Richmond and Mr. Jackson. R.A. and those

gentlemen recommended the youthful artist for a free scholarship at South

Kensington Art School. There at the age of sixteen he won the silver medal in

the national competition and also the £4O scholarship. Some drawings executed

by him a year ago form part of the art of the British section at the

International Exhibition at St. Louis. (London Daily News -Tuesday 03 May 1904)

Austin

became an Edwardian celebrity, the new Aubrey Beardsley, working as an

illustrator, holding exhibitions in the West End, and publishing his own books.

Fellow artists acclaimed his work including G.F. Watts, John Singer Sargent and

Augustus John. He met the Great Beast himself, Aleister Crowley, who became a

patron, publishing several of Austin’s drawings in his magazine ‘Equinox’.

Crowley invited him to join his Thelemite order the Argenteum Astrum but the pair fell out before Austin became a full

member. His association with England’s greatest occultist reinforced his

interest in the esoteric and he remained committed to magical theory and

practice long after the pre war fashion for it passed. During the First World

War he was initially rejected on medical grounds for military service but then called

up again in 1917 when the authorities were desperate enough to accept almost

anyone. He served in the Royal Medical Corp (where he was officially reprimanded

for scruffiness) and had a short stint as an official war artist in 1918. After

the war he career went into terminal decline; Austin’s strong draughtsmanship and

his attachment to figurative art left him outside the new mainstream of

modernism and he ended up back living south of the river in the Borough in near

poverty and increasing isolation. In the early 1930’s there was an attempt by

some newspapers to claim that the artist was the father of Surrealism (FATHER

OF SUUREALISM – HE’S A COCKNEY! ran one headline in 1936). Before the war he

was trying to sell stylised portraits of Jean Harlow, Mary Pickford and other

Hollywood stars from a studio above

Woolworths in the Elephant & Castle and in the blitz he lived in a bombed

out basement in Brixton with a pride of stray cats.

After

the war another newspaper article, this one portraying him as a starving artist

(concerned readers from as far away as South Africa posted him tins of

pineapple chunks and salmon) brought him to the attention of fellow artist

Steffi Grant and her husband Kenneth, Aleister Crowley’s one secretary. In an

article in the Guardian Phil Baker (author of an excellent biography of Austin)

pointed out that “it was in the writings

of the late Kenneth Grant…. that Spare was reinvented as a dark sorcerer,

seduced and initiated in childhood by an elderly witch in Kennington. Grant

preserved and magnified Spare's own tendency to confabulation, giving him the

starring role in stories further influenced by Grant's own reading of visionary

and pulp writers such as Arthur Machen, HP Lovecaft, and Fu Manchu creator Sax

Rohmer. Grant's Spare seems to inhabit a parallel London; a city with an alchemist

in Islington, a mysterious Chinese dream-control cult in Stockwell, and a small

shop with a labyrinthine basement complex, its grottoes decorated by Spare,

where a magical lodge holds meetings. This shop – then a furrier, now an

Islamic bookshop, near Baker Street – really existed, and part of the

fascination of Grant's version of Spare's London is its misty overlap with

reality.” Kenneth Grant was a key supporter and promotor of Austin while he

was alive and integral to the creation of his legend after his death. The

Grants were one of the few mourners at Austin’s funeral, Kenneth who had been

born in Ilford, like Austin probably returning to the place for the last time,

Austin never to leave, Kenneth never to return.