|

| The tomb of William Mansel Phillips of Coedgair in Carmarthenshire, second son of Sir Wm Mansel baronet of Iscoed in the same county, and of Caroline his wife, only child of Benjamin Bond Hopkins Esq |

St

Mary’s in Wimbledon was my first stop on a day of cemetery touring – from here

I planned to walk on to Gap Road Cemetery and then to Lambeth Cemetery in

Tooting. St Mary’s was only on the list because I had wanted to see the tomb of

Sir Joseph Bazalgette for some time; I didn’t expect to spend long in the

churchyard, a quick look around to see if there was anything else of interest

and then 15 minutes to take a few photos of the Bazalgette mausoleum. The entrance to the churchyard is at the end

of a short road with an open field to one side and an eye catching Victorian

stuccoed hunting lodge to the other with its larger than life reclining stag

staring impassively from the roof top cornice. St Mary’s, with its 196 foot spire, is a Sir George

Gilbert Scott gothic revival rebuild from 1843 of an older, Georgian church though

there has probably been a church on the site since before the Norman Conquest. As I had done no research I was taken by

complete surprise at the variety and quality of the memorials in the

churchyard. According to the church’s website “along with Chiswick and

Hampstead, Wimbledon churchyard possesses the highest concentration of listed

monuments anywhere in Greater London.” There are 25 Grade II listings in total

for headstones and memorials in the churchyard which, given that the old part

of St Mary’s where all the listed memorials are, is far smaller than St

Nicholas’ in Chiswick or St John-at-Hampstead probably means more listings per

square foot than either of its rivals.

|

| The tombs of Louisa and Margaret Bingham (Countesss Lucan) and of Georgiana Charlotte Spencer Quin |

In

the 1810 edition of The Environ’s of London Daniel Lyson says “in the

church-yard are tombs of Gilbert Smyth, M.A. of Christ's College, Cambridge,

who died in 1674; John Simpson, "a zealous "minister of Christ, who

was blessed with the conversion of very many souls in the city of London;"

he died in 1662; Thomas Pitt of London, merchant (1699).” I couldn’t find

anything quite that old but there are many finely preserved 18th century

headstones. The first monument that really caught my eye was because of the

surname; Historic England list it as the Bingham tomb and describe it as a “pedestal

tomb. Circa early C19. Portland stone. Greek Revival manner. Stepped base with

circular pedestal surmounted by triangular block, inscribed, corniced, having

low pedimented projections and corner acroteria. Urn finial on cylindrical

pedestal.” The inscription on the front says ‘Louisa Bingham second daughter of

Charles Earl of Lucan and of Margaret his wife. She died in 1784 in the 20th

year of her age.’ Also buried here is her mother; the inscription on the

reverse reads ‘Margaret Countess of Lucan, Widow of Charles Earl of Lucan and

daughter and coheiress of James Smyth of St Audries in the County of Somerset

Esq. and of Grace Dyke of Pixton in the County of Devon his wife. She died in

1814 in the 73rd year of her age.’ Margaret Bingham (1740-1814) was the wife of

the first Earl of Lucan and was much admired by Horace Walople for her beauty

and her talent as an amateur artist. Just a few yards away is the memorial for Georgiana

Charlotte Spencer Quin, a “tall rectangular pedestal surmounted by rectangular

inscribed block with quilloche frieze and cornice, and corner acroteria,”

according to Historic England. Georgina was Margaret’s granddaughter who died

in childbirth at the age of 29 in 1823. Her baby only survived 9 weeks and was

interred with her mother. Georgina’s mother was Lavinia Bingham, Margaret’s

eldest daughter, who married George Spencer, Viscount of Althorp and 2nd Earl

Spencer. Margaret’s descendants include her great great great great great granddaughter

Princess Diana (daughter of the 8th Earl Spencer) and her great great great great grandson

Richard John Bingham, the 7th Earl of Lucan who was, of course, notorious for allegedly

bludgeoning the family nanny to death

with a piece of bandaged lead pipe in 1974 and never having been seen since.

|

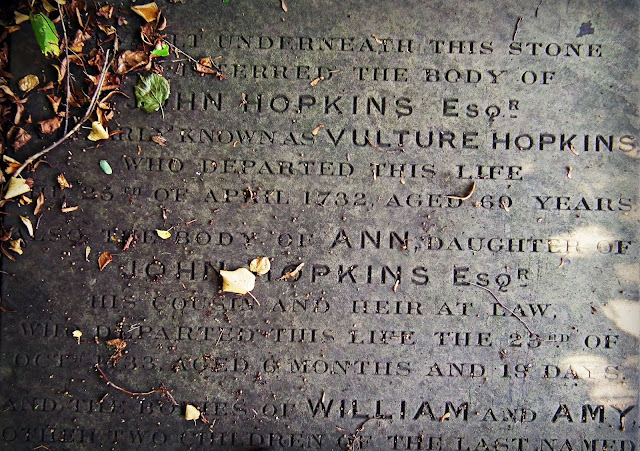

| Vulture Hopkins |

During

the 1869 Christmas holiday the poet Gerard Manley Hopkins, who was then a Jesuit

novice at Manresa House in Roehampton, walked across Wimbledon Common to St

Mary’s to take a look at the church and

churchyard. He was delighted to come across the tomb of William Mansell Philips

of Coedgair in Carmarthenshire and his wife Caroline, only child of Benjamin

Bond Hopkins. Although born in Stratford in East London Hopkins was proud of

his Welsh lineage – he also had Mansel

cousins – and he felt that the occupants of the fine chest tomb with its imposing

coat of arms must be distant relatives. As he wandered around the churchyard he

also came across the grave of John Hopkins, known as Vulture Hopkins. On 30thh

December he wrote to his mother thanking her for her Christmas present of

flannel shirts (his old ones really were, he said “very absurd things, for they

were so small that the waists were somewhere near my shoulders, and they were

rotten with age…”) and telling her about his discoveries in St Mary’s:

I

have found out something which may interest my father. In Wimbledon church near

here there is a marble tomb on which our arms and crest caught my eye. It is,

so far as I remember the names, the tomb of William Mansel Phillips of Coedgair

in Carmarthenshire, second son of Sir Wm Mansel baronet of Iscoed in the same

county, and of Caroline his wife only child of Benjamin Bond Hopkins Esq. It would

look as if he wore his father-in-law’s arms and crest. I know I have some cousins

the Mansels but I cannot remember anything about them. Besides this there is in

a comer of the same churchyard a tombstone full of Hopkinses beginning with

John Hopkins familiarly known as Vulture Hopkins’ (they should have left his nickname

rest with him. I think he is mentioned in Pope’s satires). The stone is modern,

no doubt replacing some old ones. One would not wish to have anything to do

with the bird but it looks very much as if the Hopkinses had an old connection with

Wimbledon I should like to hear about this anything you know.

John

‘Vulture’ Hopkins was a city financier and speculator, also known as ‘the

Putney Usurer’, who made a fortune speculating in the South Sea Bubble and died

in 1732 leaving a fortune worth £300,000. G.M Hopkins was correct in thinking

that he is mentioned by Alexander Pope. He is also mentioned by Dickens in Our

Mutual Friend, a passing reference which he had got from Frederick Somner

Merryweather’s Lives and Anecdotes of Misers. Merryweather only mentions

Vulture Hopkins when discussing the even more tight-fisted Thomas Guy, in public

a philanthropist (and benefactor of the hospital that still bears his name) but

in private a notorious skinflint;

It

is said that one evening he was sitting in his little back parlour meditating

over a handful of half lighted embers, confined within the narrow precincts of

a brick stove; a farthing candle was on the table at his side, but it was not

lit, and the fire afforded no light to dissipate the gloom; he sat there all

alone planning some new speculation; congratulating himself on saving a

pennyworth of fuel, or else perchance thinking how else he could bestow some thousand

guineas in charity: his thoughts, whether on subjects small or great, were interrupted

by the announcement of a visitor; he was a shabby, meagre, miserable looking

old man; but compliments were exchanged, and the guest was invited to take a seat;

Guy immediately lighted his farthing candle, and desired to know the object of

the gentleman's call: the visitor was no other than the celebrated Hopkins, who

on account of his avarice and rapacity had obtained the name of Vulture

Hopkins. "He lived," says Pope, "worthless, but died worth three

hundred thousand pounds, which he would give to no person living, but left it

so as not to be inherited till after the second generation." His counsel

represented to him how many years it must be before this could take effect, and

that his money would only lie at interest all that time. He expressed great joy

thereat, and said they would then be as long in spending as he had been in

getting it. But the Chancery afterwards set aside the will, and gave it to the

heir at law. The reader will probably remember the lines in Pope's Moral

Essays—

"When

Hopkins dies a thousand lights attend,

The wretch that living saved a candle's

end."

"I

have been told," said Hopkins, as he entered the presence of Thomas Guy, "that

you are better versed in the prudent and necessary art of saving, than any man

now living, and I now wait upon you for a lesson in frugality, an art in which

I used to think I excelled, but I am told by all who know you that you are

greatly my superior." "If that is all you are come about," said

Guy, "why then we can talk the matter over in the dark;" so saying,

he with great deliberation put the extinguisher on his newly lighted farthing candle.

Struck with this instance of economy, Hopkins acknowledged the superior abilities

of his host, and took his leave imbued with a profound respect for such an

adept in the art of saving.

Vulture

Hopkins’ heir at law was one Benjamin Bond a clerk to a city attorney, whose

mother was the daughter of John Hopkins of Bretons in Dagenham and distantly

related to the deceased miser. It took him forty years to inherit; Vulture died

in 1732 but Benjamin didn’t come into his fortune until 1772. To comply with

the terms of the will he took Hopkins as a surname. He bought an estate at

Painshill in Surrey and became a member of Parliament and a financier and speculator

in his own right. He married three times. Daniel Lyson’s says, intriguingly, that

at St Mary’s “At the entrance of the church-yard, on the right hand, is a large

columbarium made by Benjamin Bond Hopkins, Esq. for the interment of his

family. Within it are inscriptions upon tablets of white marble to the memory

of Benjamin Bond, Esq. of Clapham, who died in 1783; his wife Elizabeth, who

died in 1787; and Eliza and Alicia, wives of Benjamin Bond Hopkins, Esq. of

Painshill, who died in 1771 and 1788.” There seems to be no trace of this columbarium

(surely a mausoleum or possibly a vault?). In the tomb of William Mansell

Philips of Coedgair which so intrigued G.M Hopkins is buried Caroline, William’s

wife, and only daughter of Benjamin Bond Hopkins. She would have been a real

catch for William; the Gentleman’s Magazine commented in 1794 “we doubt whether Mr Bond Hopkins's

oldest daughter was not by his first wife. Be that as it may he has left to his

surviving and now only daughter £50,000 when she attains the age of 24 over and

besides 8ool per annum of her mother's jointure.” Benjamin also had an illegitimate son who also

received a considerable inheritance but the majority of the fortune went to

Caroline.

|

| The tomb of Gerard De Visme Esq of London, Lisbon and Wimbledon |

Apart

from Sir Joseph Bazalgette’s the other remarkable monument at St Mary’s belongs

to Gerrard De Visme who died in 1797. Historic England says the tomb “consisting

of a square plan, rusticated pyramid with corner acroteria to the base. An

acroterion has fallen due to movement in the stone blocks, and another is

dislodged. Slow deterioration continues. A condition survey has been carried

out, funded by Historic England. The church, Local Authority and Historic

England are working together to secure funding to enable the necessary works to

be carried out.” De Visme was a London born merchant of Huguenot descent who

spent most of his life in Lisbon and built a castle at Sintra. He returned to England

to retire at Wimbledon. There will be more about De Visme to come in a separate

post about his tomb and his life.

St

Mary’s has, by and large, managed to keep itself out of the newspapers. One of

the few even remotely interesting stories I could find about it was published

in the Gloucestershire Echo on Monday 07 September 1936;

At

the end of a marriage ceremony at St Mary's Parish Church, Wimbledon, last

Saturday, the organist, Mr. Henry Ralph Wagstaff, aged 65, of Wimbledon,

collapsed and died. The congregation was unaware of his death. Mr. Wagstaff had

been acting as deputy for the regular organist.