St

Bartholomew is one of the nondescript apostles, one of the 12 who seems to be

there simply to make up the numbers. The gospels don’t even agree on his name;

in the synoptic gospels he is Bartholomew but to John he was Nathanael. Even

Christ barely noticed him; “Behold a true Israelite, in whom there is no

guile,” John alleges Jesus said on first seeing him, before promptly forgetting

about him again. After the resurrection he wandered Asia casting out demons and

baptising converts, from the coast of Anatolia to the shores of India. The manner of his martyrdom transformed him

into an icon of western art, one the few saints still providing inspiration to

secular modern artists. On an overcast November morning in the gloomy south

transept of the priory church of St Bartholomew the Great, the burnished gold

of ‘Exquisite Pain’, Damien Hirst’s gilded statue of the saint, looks

unnaturally bright, it seems to be radiating light rather than reflecting it.

Despite the superficial magnificence I can’t help feeling the gilding is a

mistake and that the statue looked better in its original plain bronze

incarnation. The polished gold version reminds me irresistibly of C-3PO. The

saint is shown in one of his traditional poses, flayed alive, a scalpel and

shears in his hand, and carrying his own skin over his right arm like an

unneeded overcoat. The artist said the inspiration for his St Bartholomew came

“from woodcuts and etchings I remember seeing when I was younger. As he was a

martyr who was skinned alive, he was often used by artists and doctors to show

human anatomy." His catholic upbringing exposed him to the golden legends

of the saints “they are great stories and it is about... those guys… who all

met these terrible ends...,” says Hirst, “everyone is a martyr really in life.

So I think you can use that as an example of your own life, just that kind of

involvement with the world. Just trying to find out what your life actually

amounts to, in the end.” But the statue is not just a homage to St Bartholomew,

Hirst had another martyr in mind when creating his sculpture “I added the

scissors because I thought Edward Scissorhands was in a similarly tragic yet

difficult position," he said, "it has the feel of a rape of the

innocents about it.”

The

Sotheby’s catalogue note accompanying the sale of a copy of the statue claims

that it “challenges the relatively recent demarcation of art and science,

evoking the representations of Saint Bartholomew (the patron saint of doctors

and surgeons) that were historically used as teaching aids for medical

students.” It goes on to say “as in so much of Hirst’s work, the relationship

between religion, science and art is playfully dissected. The artist was deeply

affected by the often-gruesome religious imagery he was exposed to as a child,

growing up in a Catholic household. As a teenager, he made repeated visits to a

mortuary, where he produced sketches of the corpses, simultaneously studying

the anatomical make-up of the body and attempting to address his fear of death.

These early experiences undoubtedly informed the development of Hirst’s visual

language and his examination of the complex, frequently blurred areas of

intersection between belief, religion and science have produced some of the

artist’s most challenging and important work to date.” The catalogue

acknowledges the similarities between Hirst’s St Bartholomew and Jean-Antoine

Houdon’s l’Écorché (Flayed Man) of 1767 but doesn’t mention that images of the

saint showing off his musculature as accurately as an anatomical model go back to the early 16th

century and the influence of the great Flemish anatomist Andreas Vesalius.

There

are late medieval images of the flaying of Saint Bartholomew which depict in

gruesome detail the process of stripping his skin. In an altarpiece dating from

1412 the Catalan Jaume Huguet shows the saint with arms raised and lashed to

two poles already flayed to the waist, with two executioners, one wearing an

apron to protect his clothes and the other holding a spare knife in his mouth,

concentrating on carefully removing the skin in one piece. In the German artist

Stefan Lochner’s picture of around 1435 the saint, lashed face down to a

surgeon’s table, is nonchalantly resting on one elbow and casually observing,

over his shoulder, a man in chainmail with a knife between his teeth using two

hands and brute force to strip away the skin from his shoulder and arm whilst

another, dressed in a turban and with a scimitar at his waist, makes an

exploratory incision in the back of his thigh. Sitting on the floor in front of

the table an old man with ripped leggings sharpens more knives on a whetstone. In

an Italian depiction of the saint by Matteo di Giovanni from around 1480 he is

shown completely flayed except for his head with his skin draped stylishly over

the shoulder and held in front where it falls to the waist and hides his

genitalia. In these images what is left when the saint’s epidermis is removed

is red, raw flesh, probably bloody subcutaneous fat. In more tasteful images,

such as Michelangelo’s version of the saint on the ceiling of the Sistine

Chapel, he holds up his flayed hide (looking almost ghostlike its

disembodiment) but has miraculously grown a second one, as if it had been

sloughed off as painlessly as a snake sheds its skin, rather than having it

ripped from him in an act of grotesque violence.

|

| Vesalius |

1543 was a watershed moment for representations of the martyrdom of St Bartholomew. Andries van Wesel, the young Flemish doctor who was Professor of Surgery and Anatomy at Padua University, better known to the world by the Latinised form of his name, Andreas Vesalius, published the ground-breaking anatomical work De humani corporis fabrica. With illustrations by Titian's pupil, Jan Stephen van Calcar, the book showed the dissection of a human body, a corpse undergoing an anatomical striptease, prancing around initially sans skin to show off its muscles, then peeling away layers of flesh to reveal the deeper structures and organs until just an articulated skeleton is left standing, resting a bony elbow on a tomb, bony chin propped thoughtfully on bony fingers, presumably contemplating mortality. The plates of what essentially is a flayed man showing off his musculature, one arm in the air, posing in front of a ruined classical tomb became the model for later depictions of St Bartholomew. In 1556 a Spanish physician, Juan Valverde de Amusco, published Historia de la composicion del cuerpo humano in Rome, a work almost entirely plagiarised from Vesalius. What little originality was in Valverde’s book came from the pen of Gaspar Becerra, a Spanish artist who had studied under Michelangelo in Rome. His striking plate of a flayed man holding up his own skin and grasping a knife in the other shows some affinities with Michelangelo’s St Bartholomew, whilst clearly drawing on Vesalius to produce a startling new image of the saint, one grounded as much in science as in religious iconography.

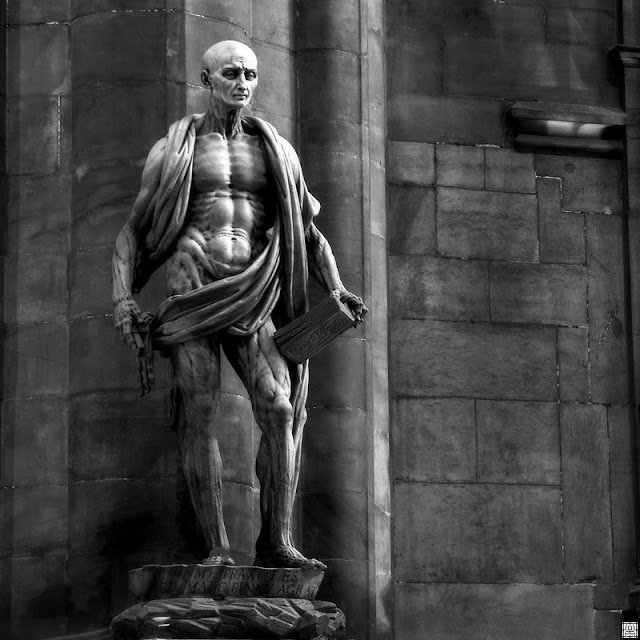

The Italian sculptor Marco d’Agrate would have used Vesalius’ anatomy as well as Valverde’s book when he produced his gruesomely lifelike St Bartholomew Flayed of 1562, which stands in the transept of Milan Cathedral. Brilliantly executed and anatomically correct the flayed saint stands with his own skin draped over his shoulders and round his waist, a bible in one hand and a mysterious tool, perhaps a hand plane somehow used for skinning, in the other. The artists overweening pride in his work is shown in the words he chiselled on the statues base, Non me Praxiteles, sed Marc'finxit Agrat; I was not made by Praxiteles but by Marco d'Agrate. Mark Twain recorded his horrified reaction to the statue in Innocents Abroad (1869) “It was a hideous thing, and yet there was a fascination about it somehow. I am very sorry I saw it, because I shall always see it now. I shall dream of it sometimes. I shall dream that it is resting its corded arms on the bed’s head and looking down on me with its dead eyes; I shall dream that it is stretched between the sheets with me and touching me with its exposed muscles and its stringy cold legs. It is hard to forget repulsive things.”

|

| St Bartholomew by Latente on flickr |

As

the renaissance faded and the baroque developed, depictions of St Bartholomew’s

martyrdom became more psychological, focussing on mood, content to merely hint

at the violence and consequently dwelling less on the physicality and horror of

torture. Giovanni Battista Paggi

straddled the renaissance and baroque and his painting of the flaying is a

fascinating amalgam of the distinct styles of the two periods. The hieratic

composition and graphic violence are renaissance in character but the naturalistic

handling of the two men skinning the saint (they concentrate as dispassionately

as they would if they were handling a pig carcase), St Bartholomew’s theatrical

pose and the gloomy sky anticipates baroque handling of the subject. A typical

example of this is Valentin de Boulogne’s (the ‘French Caravaggio’) picture of

the saint of c 1614. The saint is a fuddled old man whose slack hide looks like

it will easily peel away from his body. The two torturers are sinewy artisans

in labourer’s clothes efficiently going about their job; one tightens the rope lashing

St Bartholomew to the crude wooden cross while the other clutches a handful of

skin on his outer thigh and readies his knife for slicing into it. The whole

scene is dramatically side lit in typical high baroque chiaroscuro. During the

enlightenment religious painting became an unimportant subgenre. With rise of

interest in science in general and anatomy in particular écorché gained a new

lease of life. Jean-Antoine Houdon’s l’Écorché

belongs to this period, a piece that has such close affinities with Hirst’s

that it is uncomfortably close to being a copy.

According

to the Golden Legend St Bartholomew died in Albanopolis, an ancient city

somewhere in Greater Armenia, variously identified as Darbend in Dagestan on

the northern shores of the Caspian Sea, or Albac on the Turkish/Iranian border,

or Baku in Azerbaijan. The city was ruled by the Persians and St Bartholomew

took up residence as a beggar in the temple of the demon Astaroth. The temple

had been the centre of a cult of healing but the miraculous cures attributed to

Astaroth stopped when the saint moved in. The temple gradually filled with the

sick and ailing whose sacrifices and prayers were now failing to find a cure. When

the priests learned this was due to the presence of a Christian in the holy

precincts they searched for Bartholomew for two days and nights amongst the

crowds in the temple but failed to find him. It was only when a man possessed

by a devil wandered through the sanctuary crying out “Apostle of the Lord,

Bartholomew, your prayers are burning me up!” that the saint finally stepped

forward and cast out the demon. Bartholomew was seized by the priests but the local

king, Polymius, hearing of the exorcism and having a daughter who was likewise

possessed by a demon, ordered the saint to be brought to the palace to cure

her. The princess was kept in chains because of her unpredictable ferocity; the

whole court was terrified of her. Bartholomew ordered her chains be struck off,

“Her demon has already left her,” he told the alarmed household servants. When

the King saw that his daughter was cured he loaded camels with gold and silver,

precious stones, pearls and luxurious garments, sending them to the saint.

Bartholomew sent them all back untouched, telling the King that he sought no earthly

reward, just the right to preach the gospels and to heal the multitude of sick

now crowding the temple of Astaroth.

Polymius

was present in person the next time the priests began the sacrifice to Astaroth.

As the ceremony began the demon cried out “Refrain, you wretched ones, from

sacrificing to me, lest ye suffer worse for my sake; because I am bound in

fiery chains, and kept in subjection by an angel of the Lord Jesus Christ, the

Son of God, whom the Jews crucified.” Bartholomew stepped forward and asked the

demon who had caused all the people in the temple to fall sick. “The devil, our

ruler,” said Astaroth, “he sends us against men, that, having first injured

their bodies, we may thus also make an assault upon their souls for then we

have complete power over them, when they believe in us and sacrifice to us.”

King Polymius ordered his men to topple the statue of the idol but even armed

with ropes and levels they were unable to move the idol even a fraction of an

inch. Bartholomew stepped forward again and commanded the demon; “In the name

of our Lord Jesus Christ, come out of this idol, and go into a desert place,

where neither winged creature utters a cry, nor voice of man has ever been

heard.” At this all the idols of the temple crumbled to dust and an angel

appeared, leading a subdued Astaroth bound in fiery chains whose ferocious

appearance was “like an Ethiopian, black as soot; his face thin-cheeked and sharp

as a dog's, hair down to his feet, eyes like fire, sparks pouring out of his

mouth and smoke like sulphur out of his nostrils, with wings spined like a

porcupine.”

The

people of Albanopolis abandoned devil worship from that day forth and began to

follow the word of the one true God. But Polymius had an elder brother, also a king,

Astreges. The priests of Astaroth went to Astreges and told him “O king, your

brother Polymius has become disciple to a certain magician, who has taken down

our temples, and broken our gods to pieces.” Astreges sent a thousand armed men

with the priests to capture Bartholomew and bring him in chains to the palace.

“Are you he who has perverted my brother from the gods?” To which the apostle

replied “I have not perverted him, but have converted him to God.” The king

then asked “Are you he who caused our gods to be broken in pieces?” The apostle

responded “I gave power to the demons who were in them, and they broke in

pieces the dumb and senseless idols.” Astreges then threatened the apostle “As

you have made my brother deny his gods, and believe in your God, so I also will

make you reject your God and believe in my gods.” “You can do nothing to my

God,” said Bartholomew, “but I will break all your gods in pieces.” As these

words were spoken messengers appeared to tell the King that the all the idols

in the temples had fallen from their pedestals and smashed into pieces. In fury

Astreges rent the royal purple in which he was dressed and ordered Bartholomew

to be crucified head downwards, taken down while still alive, flayed and finally

beheaded. The converts to Christianity, 12,000 of them, came from the cities of

Armenia to collect Bartholomew’s mortal remains and bury them in a royal tomb.

When Astreges heard this he ordered the corpse to be thrown into the sea. On

the thirtieth day after Bartholomew’s death demons swarmed from hell to

strangle Astreges and the priests of Astroth and to carry their souls back to

the devil as punishment for the martyrdom of the apostle. The people of Armenia

made Polymius their Bishop, a position he held for 20 years.

After

Asteges had ordered Bartholomew’s remains to be cast into the sea they were

miraculously washed ashore at Lipari in Sicily where it was venerated as a holy

relic by the locals. In 331 the Moors invaded Sicily and destroyed the

sepulchre which held the saints bones, throwing them out along with the remains

in the church ossuary. Shortly afterwards a monk had a vision of the saint who

instructed him to find his bones and take them to Benevento on the Italian

mainland for safekeeping. When the perplexed friar asked how he would identify

them amongst all the other bones scattered around the ruins of the church the

saint told him to “gather them by night, and them that thou shalt find shining

thou shalt take up.” The monk followed the saint’s instructions and the relics

found their way to the Basilica of San Bartolomeo in Benevento where some of

them can still be seen today. Other parts of the saint were transferred or

traded to other important religious centres; to Rome, a part of the saint’s

skull to Frankfurt and an arm to Canterbury Cathedral. The English had a particular

veneration for St Bartholomew when Rahere, a herald to King Henry the First,

had a vision of the saint on a pilgrimage to Rome. Rahere founded the priory

hospital of St Bartholomew’s as a result of the vision, the King granting him a

charter for a fair to fund it. St Bartholomew’s fair ran annually for over

seven hundred years, always starting on 24th August and lasting for up to three

weeks, from 1133 to 1855, always within the precincts of the abbey. It was

London’s great summer fair until the City authorities suppressed it for

inciting public debauchery and disorder in 1855.

Really nice article about St. Bartholomew. One of the few good ones on the internet.

ReplyDeleteDěkuji vám Lenka. Hagiography isn't normally my thing but St Bartholomew is an important saint in London's history.

DeleteThank yyou

ReplyDelete