In

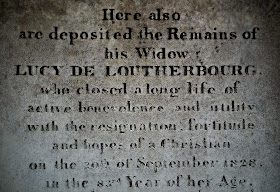

the churchyard of St Nicholas in Chiswick the artist, stage designer, inventor,

mason, mystic, faith healer and kabbalist Philippe De Loutherbourg lies buried

with his second wife Lucy, once reputed to be the most beautiful woman in

England. Their striking chest tomb was designed by Sir John Soane and is now

grade II listed. The west facing inscription for de Loutherbourg himself has

been obliterated by weathering but the east facing inscription to Lucy is still

clearly legible.

Philippe

de Loutherbourg was born in 1740, the son of the court painter of Darmstadt in

Germany. His father had ambitions for him to become an engineer and his mother

a Lutheran minister and he was educated, in Strasbourg, with a future in the

church in mind. But his parent’s dreams of respectability were to be thwarted

by a wayward streak in their son that would never allow him to settle into bourgeois

respectability (despite his love of money).

Philippe wanted to follow his father into the arts and badgered his

family into moving to Paris to allow him to study painting. In France the

family lost what little control they had over the young Philippe who became, in

his own words, “a freethinker and a hothead.” The 21 year old took up with an

older but beautiful widow, Barbe Burlat who drew him into a reckless adventure

to fleece a married, retired Captain of the East India Company, Antoine de

Meyrac. The ageing but besotted Meyrac

agreed to pay Barbe 600 livres to become his mistress. Further gifts, jewellery,

expensive wines, luxurious carpets, silk stockings, followed but the promised

consummation of the affair failed to materialise. When the furious and

frustrated Meyrac refused to part with any more cash Philippe threw him out of

Barbe’s house and barred his way back in with a drawn sword. Just a few days

later Philippe himself married Barbe. The couple’s outrageous behaviour became

notorious and started to threaten the glorious strides Philippe was making in

his artistic career.

|

| Philippe in his 30's. |

His

first exhibited painting had drawn praise from no less a figure than Denis

Diderot. The encyclopaedist did much to promote Philippe’s career although his

praise was never totally unqualified and he did not approve of the young

artist’s relationship with Barbe or his pronounced mercenary streak. The Meyrac

scandal did not stop Philippe being elected to the Académie Royale but Barbe

herself finished his Parisian career when she filed for a writ of separation of

her property from his alleging he had used up her dowry and then sold her house

to finance his gambling, had run up huge debts, had slept with numerous whores

and servants and had physically abused, once so severely as to cause a

miscarriage. Philippe did not hang around to answer these charges; he simply

helped himself to his wife’s remaining jewellery and fled to London to start a

new life, leaving the heavily pregnant Barbe and their four children behind.

Within

a year of his arrival in London Philippe was exhibiting his paintings at the

Royal Academy. A friend introduced him to David Garrick who, immediately

impressed by this imposing foreigner, took him on as the chief stage designer

at Drury Lane at a salary of £500 a year. His productions transformed the

English stage, setting new standards of illusion, exchanging a single, often

crudely daubed, stationary backdrop for moveable painted flat and drop scenes

with integrated scenery, perspective and lighting effects. He took a restlessly

experimental approach to his work in the theatre culminating first with a

pantomime ‘The Wonders of Derbyshire’ in

1779 which realistically represented the scenery of the Peak District on stage

and then, in 1781 when he had left Drury Lane for good after quarrelling with

Garrick’s successor, Richard Brinsley Sheridan, with his invention of the Eidophusikon.

|

| The Eidophusikon |

In

February 1781 Philippe held the opening

night of the Eidophusikon at his new house in Lisle Street, Leicester

Square. This was a novel entertainment

in which, according to contemporary newspaper accounts “various imitations of

Natural Phenomena, represented by moving pictures,” were recreated upon a small

stage:

“ Here, for a fee

of five shillings, around 130 fashionable spectators sat in comfort to watch a

series of moving scenes projected within a giant peephole aperture, eight feet

by six feet. The darkened auditorium combined with skilful use of concealed and

concentrated light sources, coloured silk filters, clockwork automata, winding

backscreens and illuminated transparencies created a uniquely illusionist

environment.[18] Audiences watched five landscapes in action. Dawn crept over

the Thames at Greenwich; the noonday sun scorched the port of Tangier; a

crimson sunset flushed over the Bay of Naples; a tropical moon rose over the

wine-dark waters of the Mediterranean; and a torrential storm wrecked a ship

somewhere off the Atlantic coast. Between scenes, painted transparencies served

as curtain drops, and Mr and Mrs Michael Arne entertained the audience with

violin music and song.” (Iain McCalman “The Virtual Infernal.”)

One

visitor to Lisle Street was the 21 year William Beckford. In December 1781 he was planning a

spectacular 3 day Christmas party for which, on the strength of the theatrical

sets and the Eidophusikon, he commissioned de Loutherbourg to supply the

illusions that would transport him and his guests from an English midwinter in

an 18th century Palladian mansion in

Wiltshire to a magical oriental fantasy world. Beckford wrote to his 34 year

old mistress Louisa, (who was married to his cousin) urging him to come to “Fonthill, where every preparation is going

forwards that our much admired ….. Loutherbourg …. in all the wildness of his

fervid imagination can suggest or contrive – to give our favourite apartments

the strangeness and novelty of a fairy world. This very morning he sets forth

with his attendant genii, and swears…that in less than three weeks…[to] present

a mysterious something that the eye has not seen or heart of man conceived (his

own hallowed words) purposely for our own special delight and recreation.”

|

| The young William Beckford |

There

are no detailed descriptions of the Christmas spectacular created by de

Loutherbourg, but Beckford was pleased with the result. “I seem even at this long distance,” he later wrote “ to be warmed by the genial artificial

light that Loutherbourg had created throughout the whole of what appeared a

necromantic region, or rather, one of those fairy realms where K[ing]s’

daughters were held in thrall by a powerful Magician – one of those temples

deep below the earth set apart for tremendous mysteries…at every stage of this

enchanted palace tables were swung out covered with delicious consummations and

tempting dishes, masked by the fragrance of a bright mass of flowers, the

heliotrope, the basil and the rose – even the splendour of the gilded roof was

often masked by the vapour of wood aloes ascending in wreaths from cassolettes

placed low on the floor in salvers and jars of Japan. The glowing haze, the

mystic look, the endless intricacy of the vaulted labyrinth produced an effect

so bewildering that it became impossible for anyone to define exactly where at

the moment he was wandering…It was the realization of a romance in all its fervours,

in all its extravagance. The delirium in which our young fervid bosoms were

cast by such a combination of seductive influences may be conceived but too

easily.”

Beckford’s

most favoured guest at these Christmas revels was the thirteen year old Viscount

William Courtenay, son of the Earl of Devon, with whom he was besotted. Louisa

unashamedly helped her young lover seduce the even younger ‘Kitty’ Courtenay. Beckford later fondly

reminisced (calling him ‘she’ in apparently timeless high camp fashion) “does

she love to talk of the hour when, seizing her delicate hand, I led her,

bounding like a kid to my chamber?” The scandalous affair remained secret for a

further 3 years but in 1784 Beckford’s letters to Kitty were intercepted by the

boy’s uncle who advertised them in the newspapers and forced Beckford to flee

the country for several years of self-imposed exile while the resulting

contretemps died down. The most

immediate and enduring effect of de Loutherbourg’s three day Christmas fantasia

was to inspire Beckford to compose one of English literature's minor

masterpieces, his oriental fantasy ‘Vathek; An Arabian Tale.’

|

| The second Mrs de Loutherbourg, Lucy Paget |

|

| Guiseppe Balsamo, Count Cagliostro |

In

1773 de Loutherbourg met Lucy Corson (nee Paget) a beautiful young widow (at 28

she was 5 years younger than him) from Kingswinford in Staffordshire. Although

he appears never to have been divorced from Barbe he married Lucy at St

Marylebone Church in May the following year. His bride was considered by some

to be the most beautiful woman in England. Despite her money the marriage seems

to have been a love match; the couple lived together until de Loutherbourg’s

death in 1812 and were buried together when Lucy died in 1828. Lucy seems to

have shared her husband’s interest in all aspects of the occult from mesmerism

to the kabbalah. In 1787 the pair both fell under the sway of the Italian

occultist Giuseppe Balsamo who was paying a second visit to London under his

better known alias of Count Cagliostro. The two were both Masons and it is

probable the brotherhood brought them together. The London visit was a difficult

one for Cagliostro and he departed unexpectedly in May for Switzerland leaving

his wife Seraphina behind in the care of the de Loutherbourgs. Once the Count

was settled in Switzerland he sent for

Seraphina and Philippe and Lucy accompanied her after being promised a

programme of physical rejuvenation that would restore them to the physical and

sexual prowess of their youth. In the Swiss town of Bienne where the de

Loutherbourg’s moved in with the Cagliostro’s there were immediately problems

between the two couples. The promised programme of rejuvenation was slow to

start and there was no sign of a loan made by de Loutherbourg to Cagliostro in

London being repaid. Adding to these tensions Philippe developed a ‘leering

interest’ in Seraphina (who did not reciprocate, being much more interested in her

husbands young secretary) and Lucy appears to have contracted a unreciprocated passion

for Cagliostro himself. The two husbands eventually quarrelled and the de

Loutherbourg’s moved out. Philippe immediately launched a court case for the

return of the 170 louis he had loaned Cagliostro. As tensions increased

Philippe challenged Cagliostro to a duel who responded sarcastically that he

only fought with arsenic. Philippe armed himself with pistols, powder and ball

and went around the town telling everyone that the moment he set eyes on the

Count he was going to shoot him like a dog. Cagliostro demanded protection from

the authorities but when it wasn’t forthcoming quickly enough he began accusing

the mayor of Bienne of being in league with de Loutherbourg to destroy and the

townspeople of being mean and treacherous. The pair finally parted on the worst

possible terms and de Loutherbourg sought belated revenge in a pair of satirical

caricatures of the Count.

|

| Philippe and Lucy de Loutherbourg by John Hoppner |

In

1788 the de Loutherbourg’s returned to London and Philippe shocked the

artisitic establishment by announcing that he was abandoning painting to dedicate

himself to mystical pursuits including the study of the kabbalah and working as

a faith healer with Lucy from their house in Hammersmith Terrace. The pair

claimed that by means of the influxes

that, according to Swedenborg, flow from Heaven to Earth they could affect miraculous cures. The poor

were admitted to the de Loutherbourg’s clinic by free ticket; Mary Pratt, an

admirer of the couple, wrote a pamphlet A List of

a Few Cures performed by Mr and Mrs De Loutherbourg, of Hammersmith Terrace,

without Medicine in which she claimed that 2000 people had

been cured by them in just a few months "having been made proper

recipients to receive divine manuductions". Eventually the numbers trying

to gain admission to the clinic were so high that riots broke out amongst those

waiting to be cured and the de Loutherbourg’s had to abandon their attempts to

heal the London mob. He returned to art and confined his mystical pursuits to a

more sedate circle of friends and acquaintances.

Philippe

died on 11 March 1812 and Lucy on 28 September 1828.

Further reading

Almost all the information in this post has been drawn from the fascinating work of Professor Iain McCalman of the University of Sydney:

"The Seven Ordeals of Count Cagliostro."

"Mystagogues of revolution: Cagliostro, de Loutherbourg and Romantic London."

"The Virtual Infernal: Philippe de Loutherbourg, William Beckford and the Spectacle of the Sublime."

Sheldon

was born in Staffordshire in 1598 and was educated at Oxford. He became

involved in the church and politics, was a Royal Chaplain to Charles I and was

well known as a prominent Royalist in the run up to the Civil War. During the

Protectorate he lost his church livings and survived on the generosity of

friends and supporters until the Restoration in 1660 when Charles II made him

Bishop of London. He became Archbishop of Canterbury in 1663 and Chancellor of

the University of Oxford in 1667. He

opposed Charles II’s proposed Declaration of Indulgence which sought to extend

religious freedom to Catholics and it is said he once refused to give the King

communion because of his majesty’s libertine lifestyle. He was one of

Christopher Wren’s earliest architectural patrons – Sheldon commissioned and paid

for the Sheldonian Theatre in Oxford and chose Wren as the architect. He died

in 1677 and is buried in the Minster of St John the Baptist in Croydon.

Sheldon

was born in Staffordshire in 1598 and was educated at Oxford. He became

involved in the church and politics, was a Royal Chaplain to Charles I and was

well known as a prominent Royalist in the run up to the Civil War. During the

Protectorate he lost his church livings and survived on the generosity of

friends and supporters until the Restoration in 1660 when Charles II made him

Bishop of London. He became Archbishop of Canterbury in 1663 and Chancellor of

the University of Oxford in 1667. He

opposed Charles II’s proposed Declaration of Indulgence which sought to extend

religious freedom to Catholics and it is said he once refused to give the King

communion because of his majesty’s libertine lifestyle. He was one of

Christopher Wren’s earliest architectural patrons – Sheldon commissioned and paid

for the Sheldonian Theatre in Oxford and chose Wren as the architect. He died

in 1677 and is buried in the Minster of St John the Baptist in Croydon.